An Introduction to Mutation Testing [3/3]

A Selection of Applications

Mutation testing has been used in a remarkable number of domains across industry and theory. A fairly complete look at notable domains can be found in our usual two survey papers, and current mutation testing open-source tools can be reasonably found here.

I think it’s worthwhile, however, to summarize some notable projects and their domains, both to give a sense of how mutation testing can be applied and where mutation testing tools may be found. This summary is not comprehensive by any means, and if you know of another major project that I omitted, please reach out to me to let me know. As a disclaimer, I am not an expert at mutation testing, particularly the tools available for use:

- Mull is a project based on LLVM/Clang for mutation-testing based C/C++ program analysis

- Mutmut focuses on ease of use for mutation testing on Python programs

- Mutant is an interesting code review tool for evaluating code coverage

- MUTANDIS provides mutation operators to JavaScript applications

- MuCPP is another mutation testing framework for C++ program analysis that has gotten some attention

There are many more such projects targeting a variety of applications and domains. The ease of use of these projects varies immensely, however, given that some are very academic while others are highly industrial. If interested in the topic of using mutation testing, I recommend exploring a variety of options and finding which one will work best for your system and needs.

Trends in mutation testing

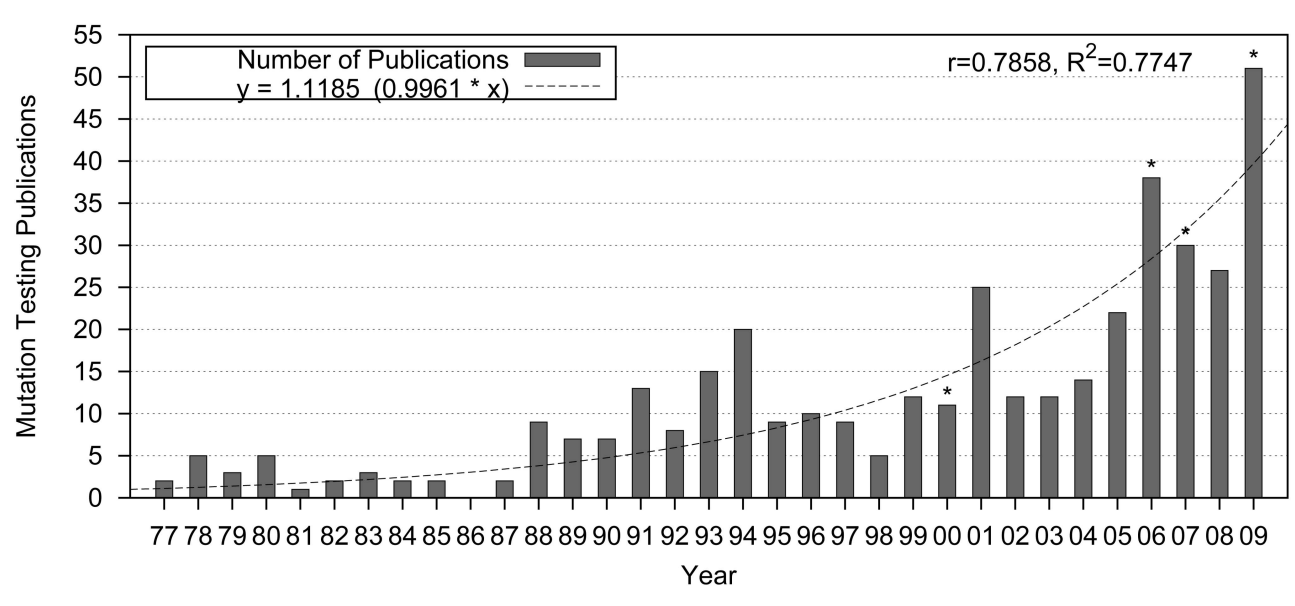

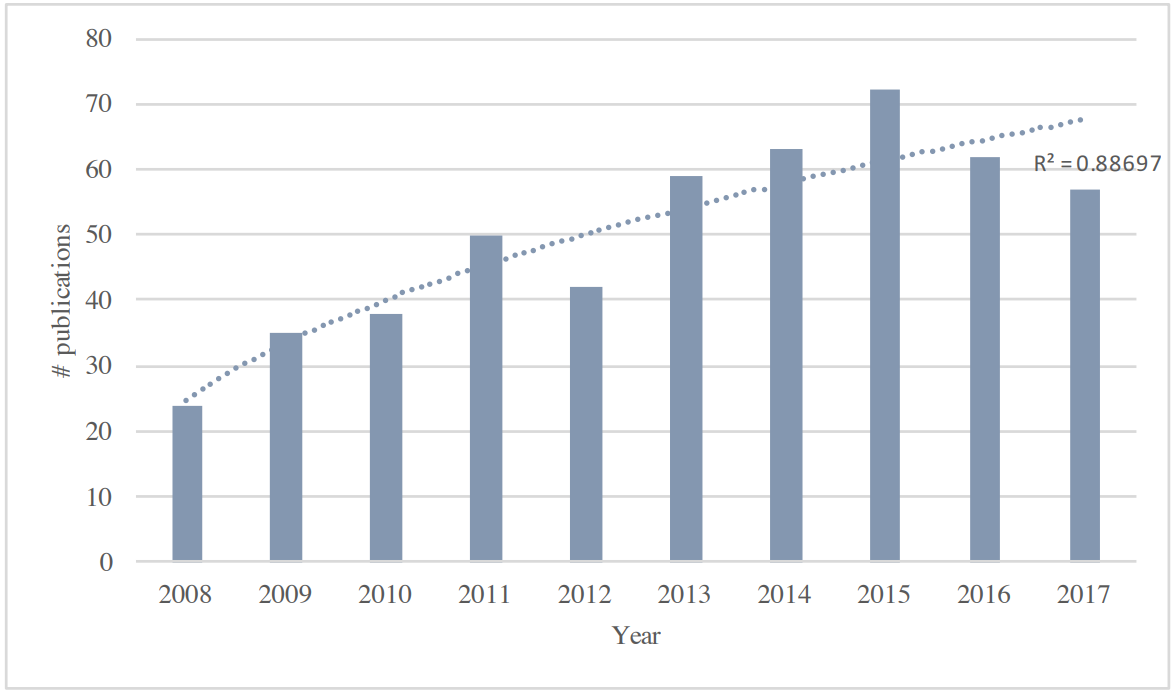

Taken directly from our favorite two survey papers, respectively, the following graphs illustrate the general growth of mutation testing as a topic:

However, we see an interesting change of trend. Specifically, while it appears that mutation testing paper publication rates grew quadratically in the late 1990s to early 2000s, this rate of growth is much more linear in the succeeding decade. In short, the rate of mutation testing publications seems to be tapering off somewhat. Note that the methods for calculating publications did change somewhat between these two surveys, but not so drastically that we should a priori expect such a change.

There are several explanations as to why this might be happening. My take is that mutation testing has been overshadowed by other exciting research and never really took off in the way that popular areas like program synthesis, security protocols, or, of course, machine learning. This is despite there being substantially interesting problems left to solve in mutation testing (we will discuss some basics in the next section).

I will argue, however, that test coverage is still an important problem, and a lack of interest in test coverage is not why mutation testing has not taken off. The challenges associated with practical mutation testing are substantial – this, coupled with a lack of usable resources on the topic, has made mutation testing fairly impenetrable except to experts in the domain. Optimistically, as tooling continues to improve, mutation testing may still have its spot in the limelight as a powerful tool for program coverage analysis.

Problems with Mutation Testing

We’ve referred a few times to some of the challenges of practical mutation testing, so now perhaps is the time to examine those challenges more directly. This will hopefully give some insight into both the challenges yet to be resolved as well as whether or not a user should practically consider mutation testing as a mechanism to explore test coverage in their system.

Hefty prerequisites

We start with perhaps the largest problem with using mutation testing for smaller systems. To use mutation testing at all, a user must both have a reasonable specification and a suite of tests of the underlying code. The former is necessary to define whether a live mutation is “interesting” (more on that later), and the latter is necessary to kill mutants. Developing these systems, particularly for a large codebase, is a non-trivial task – since mutation testing examines code coverage, there is the additional requirement that these tests be at least fairly complete for mutation testing to find anything particularly interesting, which further increases the initial cost to using mutation testing effectively.

There isn’t really a way around these requirements before using mutation testing. While I would like to claim that having a good test set of behavior is a practical necessity, many projects are able to get by with minimal testing (indeed, while time and money spent testing is often not wasted, it is still time and money spent). Additionally, some projects, such as graphics-related work, struggle with writing a formal specification and formal tests at all, let alone a complete test set that can be used with mutation testing.

A related major problem with mutation testing is a potential explosion of tests. In particular, if mutations are taken at face value rather than carefully explored, it’s relatively easy to develop tests to cover every mutation individually, which can quickly lead to a collection of small but barely interesting tests just to kill these mutations. As a result, it is important when developing with mutation testing to evaluate results holistically and develop tests to cover multiple related mutations when possible.

This is not to say, however, that mutation testing for projects is hopeless. Indeed, most reasonably sized projects invest, of necessity really, a significant amount of effort into testing and having good specifications of code behavior. When considering when to use mutation testing, just be aware of the significant amount of work needed to have a solid initial testing set that mutation testing can work on.

Performance

A major concern with mutation testing is performance (see pages 653-655 and pages 35-39). Mutation testing on a reasonably sized codebase requires mutating a lot of operations and literals and re-running the code base through the test suite with each mutation. Even if testing is relatively fast, the cost of evaluating the test set many times (the number of times depends on the number of mutations and, hence, the size of the codebase) can result in extremely long iteration times, not to mention huge amounts of results to look through.

As a consequence of long-running mutation testing times, significant research has been done to explore weakened mutation testing and other methods of achieving reasonable results without overwhelming the user. There are substantially more approaches than can be discussed here, so we will focus on the class of execution speedup approaches – see each survey paper for more detail on other approaches.

Weak mutations breaks the mutation testing requirement down into components, where individual components can be checked rather than the full program for errors. In another vein, this paper explores using mutation testing in an intermediate representation, specifically with the goal of minimizing costly repeated program transformations. Similarly, Proteum explores mutation testing in a specialized compiler environment to provide speedups, while MuJava looks at bytecode manipulations to explore a space quickly. Finally, hardware can also be used to speedup mutation testing, as can be seen with vector processing and network distribution.

It is difficult to evaluate the practical speedup obtained by these various approaches; additionally, each approach has trade-offs with respect to program completeness, accuracy, and performance. Mull, for example, obtains speedup by working on LLVM bitcode; however, the documentation of Mull itself mentions that there is a loss of precision through this approach. As a result, a practical user of mutation testing need explore several options when examining mutation testing tools to find which will be performant enough for practical use (including possibly designing one themselves).

Mutation equivalence and useless mutations

Another major concern in mutation testing research is the existence of equivalent mutants and “non-interesting” or “useless” mutants. Equivalent mutant checking is, as noted previously, undecidable in general – practically, however, there are techniques for identifying and avoiding equivalent mutants.

Among the larger scale of these techniques is TCE, a project to explore using compiler optimization techniques to identify mutation equivalence automatically in a variety of domains. Kintis and Malevris explore mutation equivalence detection over a series of papers to examine if dataflow techniques can determine equivalent mutations.

Another potential solution to exploring equivalent mutants is to use static analysis, specifically on mutation test equivalences. This paper includes analysis of weak mutation, and an interesting discussion on the notion of coverage. There is also work on dynamically improving the mutation score an important concept when evaluating the impact of equivalent mutants. Papers such as this go into greater depth on this topic and explore the impact of equivalent mutations.

This is by no means a complete summary of the forms of equivalence analysis that have been done, but should give an initial idea to the depth in which this topic has been explored as well as the idea that some tools exist to combat this problem. When developing tests using mutation testing, be on the lookout for

Another topic that was important for my research but showed up less in the literature were “non-interesting” mutations – namely mutations that were either redundant or provided information about a negligible or even intentional gap in the specification. Redundant mutations are specifically mutations which are killed twice and can cause problems in metrics of mutation kill rate. This has been researched somewhat with respect to specific operators, but it seems there is more work to be done. Non-interesting mutants, on the other hand, are not referenced in current literature to the best of my knowledge and seem a difficult topic to research.

As with the previous problems we have described, equivalent mutants and redundant mutants are not the end of mutation testing (though mutation testing is noted to be “inhibited by the presence of equivalent mutants”). Indeed, careful analysis and further research can mitigate these challenges and provide successful results, though any user of mutation testing ought to be aware of these problems at least and consider other solutions if needed.

Concluding Thoughts

Throughout this tour of mutation testing, we have explored what mutation testing is, how and why it works, some applications and trends in the field, and finally some flaws with the mutation testing approach. Hopefully this sort of dialogue will encourage future researchers to use mutation testing in a knowledgeable way. While mutation testing does have flaws, it is a powerful tool that can expand our ability to write tests that properly cover code and specifications, while also providing a metric for evaluating the effectiveness of the tests we write.

I would like to conclude by encouraging readers to explore mutation more through reading the excellent survey papers linked throughout this piece, as well as considering using those real mutation testing tools for practical development and analysis. So long as we write code, we will need to test this code. Knowing how to better write tests and explore the scope of these tests will help us, as a community, write both better software and better analysis of that software.