Implementing the Calculus of Constructions

The code for all the work in this blog post is open source on GitHub.

Background

The Calculus of Constructions (CoC) is a type theory created by Thierry Coquand. It is a higher-order typed lambda calculus that is the apex of the lambda cube. In CoC it is possible to define functions from terms to terms, types to types, types to terms, and terms to types. Functions being able to go from terms to types is what makes CoC so powerful. Types that depend on terms are known as dependent types, and most languages do not have them. As an example, consider the following vector type in Coq where the length of the vector is part of its type.

Inductive vec : Type -> nat -> Type :=

| vnil : forall X : Type, vec X 0

| vcons : forall X : Type, X -> forall n : nat, vec X n -> vec X (S n).

Definition v0 : vec bool 0 := vnil bool.

Definition v1 : vec bool 1 := vcons bool true 0 v0.

Fail Definition v0 : vec bool 1 := vnil bool.

Notice how the last definition fails because vnil bool has type vec bool 0.

This makes sense because vnil represents the empty list, which has length 0.

Attempting to assign v0 with type vec bool 1 to the expression vnil bool

fails because the types vec bool 1 and vec bool 0 are incompatible.

CoC is part of the Calculus of Inductive Constructions (CiC), which adds inductive types to CoC, and CiC is the basis of Gallina! But for the purposes of this project, we only implemented CoC.

Design and Implementation

Typing rules

Unlike most other languages, CoC eliminates the distinction between types and terms. We describe the CoC syntax below. We use for terms in general and for variables:

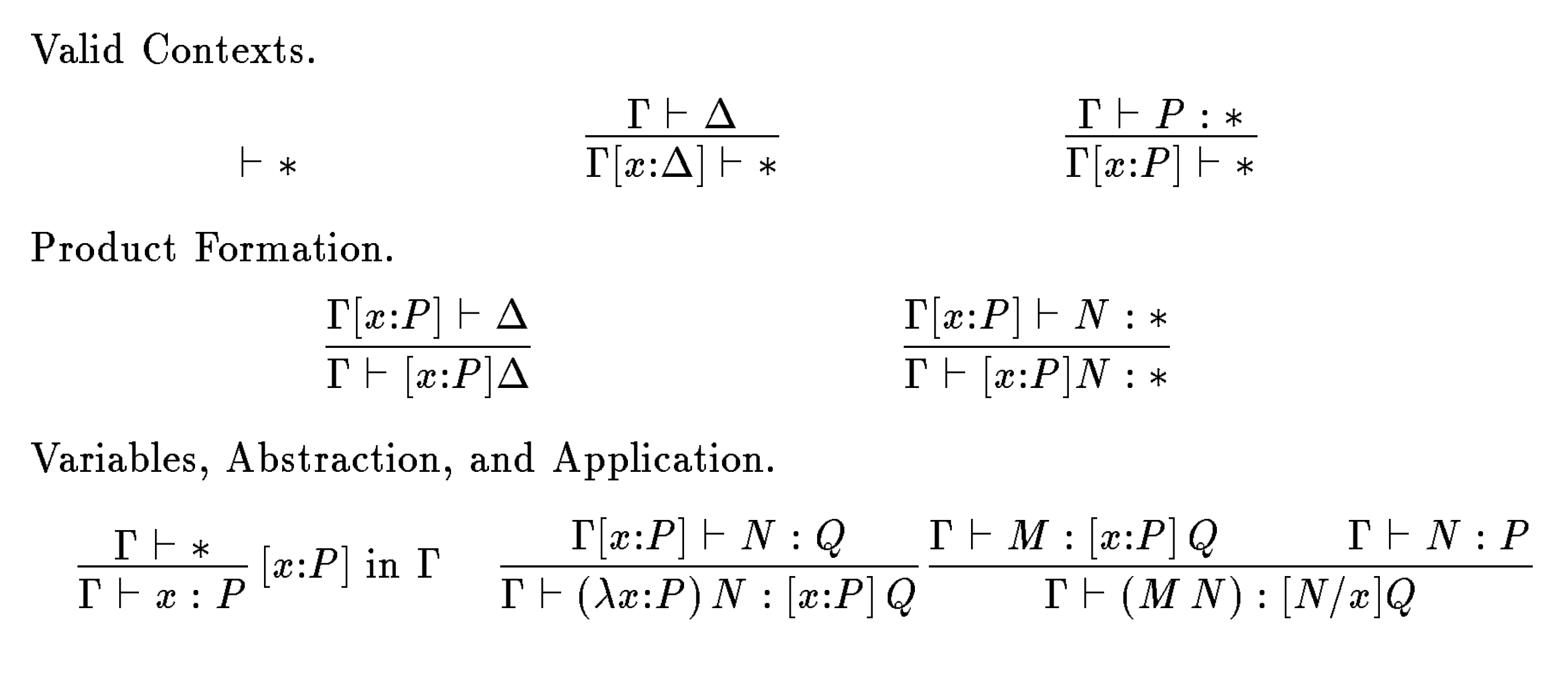

is called a product, and is the universe of all types, but is not a type itself. For an explanation of why, see the Bonus section. Note that the universe symbol is not to be confused with the kleene star, and all instances of throughout this blog post refer to the universe of all types. Contexts (denoted by ) are products over and have the form . The inference system defines two judgements:

- means is a valid context in the valid context .

- means is a well-typed term of type in the valid context

In the inference system, a type will either be a context or have the property that . Also note that is the notation for substituting for in . The inference rules are below.

Design

When I started this project, I was writing my implementation based off of some notes written by Professor Clarkson, and this was the syntax of CoC that he used.

I will be using this syntax throughout the rest of the blog post to go over examples, but the inference rules remain the same as before.

Although the concept of theorems and proofs is not involved in the formalism above, CoC becomes even more powerful when it is incorporated with theorems and proofs. I wanted to be able to write proofs in my programs as one can do in Coq, so I designed the AST with this in mind. I tried to model the theorem type off of Coq theorems, which contain an identifier, a term that represents the theorem to be proved, and a proof term. Here is the AST:

type t =

| Id of id

| Fun of id * t * t

| App of t * t

| Forall of id * t * t

| Type

and theorem =

{

id: id;

theorem: t;

proof: t;

}

and prog =

| Let of id * t * prog

| Theorem of theorem * prog

| Expr of t

Here is an example of a valid program:

let Nat = forall N:Type, (forall _:N, (forall _:(forall _:N, N), N)) in

let zero = lambda N:Type -> (lambda x:N -> (lambda _:(forall _:N, N) -> x)) in

let succ = lambda nat:Nat -> (lambda N:Type -> (lambda x:N ->

(lambda f:(forall _:N, N) -> (f (((nat N) x) f))))) in

(succ (succ zero))

(* output: (fun N:Type -> (fun x:N -> (fun f:(forall _:N , N) -> (f (f x))))) *)

and this is an example of a valid (unrelated) proof:

Theorem p_implies_p: forall P:Type, forall _:P, P.

Proof. lambda P:Type -> lambda x:P -> x.

Implementation

The main implementation task was implementing a typechecker. To typecheck a term, we first check whether that term is a context. If it is, we typecheck the context to ensure that it is well-typed (according to the “Valid Contexts” and “Product Formation” rules above). Otherwise, the term is typechecked according to the “Product Formation” and “Variables, Abstraction, and Application” rules above.

Typechecking also needs to happen for entire programs. When typechecking

a Let statement, beta reduction is performed on the term, and that result

is substituted for the corresponding identifier throughout the rest of the program.

Then the rest of the program is typechecked.

When typechecking a Theorem,

beta reduction is performed on the theorem term, and the proof term is typechecked.

Then the typechecker checks if these two resulting terms are alpha equivalent.

If they are, then the proof is valid. This is because the type of a CoC term is

the theorem that it proves, which is why the first step is to typecheck the proof

term. Since there are many ways a proof can be written (such as using different

identifiers in lambda terms), the next step is to check that the

beta-reduced theorem term is alpha-equivalent to the type of the proof. The proof

term is then beta-reduced and this term is substituted in for the corresponding

identifier throughout the rest of the program. Then the rest of the program is

typechecked.

When the typechecker sees an Expr, it typechecks the

term to make sure it is well-typed and then returns the beta-reduced term.

Evaulation

My goal for this project was to be able to solve some of the simple exercises in the Software Foundations logic chapter, and I was somewhat successful. I started by defining logical conjunction and disjunction.

(* Logical conjunction *)

let conj = lambda P:Type -> lambda Q:Type -> forall x:Type,

forall _:(forall _:P, forall _:Q, x), x in

(* Logical disjunction *)

let sum = lambda P:Type -> lambda Q:Type -> forall x:Type,

forall _:(forall _:P, x), forall _:(forall _:Q, x), x in

Here are a few of the proofs I was able to successfully typecheck. I came up with some of these proofs on my own and some with the help of a friend. These proofs were not translated from SF solutions.

(* P /\ Q -> P *)

Theorem conj_implies_fst: forall P:Type, forall Q:Type,

forall _:((conj P) Q), P.

Proof. lambda P:Type -> lambda Q:Type -> lambda p:((conj P) Q) ->

((p P) (lambda x:P -> lambda _:Q -> x)).

(* P /\ Q -> Q *)

Theorem conj_implies_snd: forall P:Type, forall Q:Type,

forall _:((conj P) Q), Q.

Proof. lambda P:Type -> lambda Q:Type -> lambda p:((conj P) Q) ->

((p Q) (lambda _:P -> lambda x:Q -> x)).

(* P -> Q -> P /\ Q *)

Theorem p_implies_q_implies_conj: forall P:Type, forall Q:Type,

forall p:P, forall q:Q, ((conj P) Q).

Proof. lambda P:Type -> lambda Q:Type -> lambda a:P -> lambda b:Q ->

lambda x:Type -> lambda evidence:(forall _:P, forall _:Q, x) ->

((evidence a) b).

(* P /\ Q -> Q /\ P *)

Theorem and_commute: forall A:Type, forall B:Type,

forall _:((conj A) B), ((conj B) A).

Proof. lambda A:Type -> lambda B:Type -> lambda p:((conj A) B) ->

lambda x:Type -> lambda evidence:(forall _:B, forall _:A, x) ->

((evidence (((conj_implies_snd A) B) p)) (((conj_implies_fst A) B) p)).

(* P -> P \/ Q *)

Theorem p_implies_sum: forall P:Type, forall Q:Type, forall p:P, ((sum P) Q).

Proof. lambda P:Type -> lambda Q:Type -> lambda p:P -> lambda x:Type ->

lambda evidence:(forall _:P, x) -> lambda _:(forall _:Q, x) -> (evidence p).

(* P \/ Q -> Q \/ P *)

Theorem or_commute: forall A:Type, forall B:Type,

forall _:((sum A) B), ((sum B) A).

Proof. lambda A:Type -> lambda B:Type -> lambda p:((sum A) B) ->

lambda x:Type -> lambda evidence1:(forall _:B, x) ->

lambda evidence2:(forall _:A, x) -> (((p x) evidence2) evidence1).

As a comparison, consider the equivalent lemma and proof for

p_implies_q_implies_conj (the third example above) in Coq:

Lemma and_intro : forall A B : Prop, A -> B -> A /\ B.

Proof.

intros A B HA HB. split.

- apply HA.

- apply HB.

Qed.

Notice how much cleaner this proof is than my code. It is no wonder that Coq has tactics to make it more usable!

My goal was to prove as many one-star exercises in this chapter as possible. Out of the eight one-star exercises, these were the ones I was able to prove:

Lemma proj2 : forall P Q : Prop,

P /\ Q -> Q.

Theorem or_commut : forall P Q : Prop,

P \/ Q -> Q \/ P.

This means I was only able to prove 25% of the one-star exercises. I was not able to prove

some of the other exercises for a variety of reasons. One exercise, iff_refl

asks you to prove forall P : Prop, P <-> P. While this seems like it should be

a fairly simple proof involving just conjunction and implication, we spent

about 20 minutes trying to solve it and couldn’t.

Another exercise, eqb_neq, asks you to prove

forall x y : nat, x =? y = false <-> x <> y.. To prove this theorem you would

need to inductively define the natural numbers, but my implementation does

not support inductive definitions.

Experience

This project was more challenging than I expected. The most difficult thing to get right was beta reduction. For example, the process of beta reducing a function application took me some time to get right — the process is to first typecheck the argument. Then you make sure that the term on the left hand side is actually a lambda term. Now you can’t just check whether the types of the parameter and argument are equal; you have to check that they are alpha equivalent. Then you can perform substitution and continue beta-reducing the term. My beta reduction bugs caused many issues elsewhere. A common bug I was having is that typechecking a function application would fail because one of the terms was not beta reduced correctly, so argument and parameter types were not alpha equivalent.

The other difficult part of this project was the evaluation. I found

it difficult to reason about proofs in CoC because all of the lambda and forall

terms made my code really messy and hard to understand. I definitely have

a greater appreciation for of Coq for having code that is easy to read and

reason about. For example, some tactics you see a lot in Coq are intros, which

introduces variables and hypotheses, and apply, which uses implications to

transform goals and hypotheses. You could write the following proof in Coq:

Theorem p_implies_p : forall P : Prop, P -> P.

Proof.

intros P H.

apply H.

Qed.

The line intros P H is introducing the proposition P and the hypothesis H,

which is P (the left-hand side of the implication). The resulting goal is P.

The line apply H applies H to the current goal, completing the proof. Here

is the same proof in CoC.

Theorem p_implies_p: forall P:Type, forall _:P, P.

Proof. lambda P:Type -> lambda x:P -> x.

Compared to Coq, it is much more difficult to understand what is happening in this CoC proof because it lacks tactics.

Future Work

The next step for this project would be to implement CiC (add support for inductively

defined types). This would allow users to define inductive lists, natural numbers, etc.

Users would also be able to define the vec type that I showed earlier as an

example of dependent types. I would also like to define some built-in

tactics to make it easier to write proofs.

When someone is first learning Coq, they usually start out with proving theorems like

1 = 1 or 1 + 2 = 2 + 1. These proofs only require one line, reflexivity.

I think it would be cool to implement inductive types and add a reflexivity tactic

so that a user could complete some of the exercises in the first chapter of

Software Foundations.

Acknowledgements

Professor Clarkson’s CoC Notes helped me a lot with understanding CoC, and this paper was also really helpful for understanding inference rules. Also huge shout out to Chris Lam for helping a little bit with the typechecker and helping a lot with writing proofs!

Bonus

is the universe of all types, but is itself not a type. Why is this? A similar question is known as Russell’s Paradox: let , i.e., is the set of all sets that are not members of themselves. Can be a member of itself?

- If is a member of itself, then by definition , which means is not a member of itself

- If is not a member of itself, then . This means by the definition of

The result is a contradiction. In symbols:

So what is the solution? Russell’s solution was type theory, which creates

a hierarchy of types where objects of a type can only be built from objects

of types lower in the hierarchy. Allowing to be a type itself would

violate this hierarchy and lead to paradox (this would be very bad, as this

would allow us to prove False).