Making LLVM Address Calculation Safe(r)

Memory Safety in LLVM

LLVM IR code is not generally memory safe. While certain obviously bad behaviors are disallowed, it is not hard to write code that may execute out-of-bounds memory accesses at run time.

For instance, the size of an array may be statically known, but the access index may be unknown at compile time:

int foo(int x) { int tmp[10]; ...//some code to set values in tmp return tmp[x]; }

In this project we seek to improve the memory safety of LLVM programs by inserting dynamic bounds checks at run time that cause the program to stop executing rather than violate memory safety. After running our compilation pass the aforementioned code would have the following run-time behavior:

int foo(int x) { int tmp[10]; ...//some code to set values in tmp if (x >= 0 && x < 10) { return tmp[x]; } else { exit(1); } }

LLVM Address Calculation

When compiling high level array and struct access to LLVM code, compilers

generally use the getelementptr

(or GEP) instruction to calculate offsets into these memory allocations.

GEP instructions have the nice property that they are type aware; offsets are phrased

in terms of "number of elements" rather than "number of bytes."

For example, the code in this stub dereferences some memory in

the middle of a struct (specifically the last element of the b field).

struct EX { int a; char b[3]; int *c; } struct X; ... return X->b[2];

In LLVM, we could write a single GEP instruction to calculate

the correct offset into the struct and then execute a load instruction

to actually dereference the pointer.

%1 = getelementptr %struct.EX, %struct.EX* %X, i64 0, i32 1, i64 2 %2 = load i8, i8* %1 ret %2

This functionality makes GEP an ideal point for analyzing out-of-bounds accesses. Before a program might make an out-of-bounds access it has to acquire an out-of-bounds pointer. Usually, this means it executes a GEP whose result will then later be the argument of a load or store operation.

Our approach in this implementation is to prevent the execution of any run-time GEP instructions that might lead to illegal memory accesses. If a program can never acquire an out-of-bounds pointer, it can't violate memory safety. As we discuss later, this is not really a sufficient condition for memory safety in LLVM IR, but it does cover a large class of problems.

Making GEP Safe(r)

Let's go back to our first example of an out of bounds array access:

int tmp[10]; ... return tmp[x];

The return statement roughly translates to:

%addr = getelementptr [10 x i32], [10 x i32]* %tmp, i64 0, i64 %x; %val = load i32, i32* %addr; ret %addr;

In order to insert a dynamic check for memory safety, there are two things we need to know:

- What is the actual access index value?

- What are legal access index values?

Happily, when considering GEP instructions, the first question is easy to answer; each operand represents an access index value. We can dynamically insert instructions into the program that compare those operands to other values.

The second question is a much more difficult problem,

whose subtleties we'll address in the next section.

For the most part though, we leverage LLVM's type

information. Based on its type annotation, we know

that %tmp points to an array with 10 32-bit integers (notated as [10 x i32]).

Therefore, we can conclude that the only valid values for %x are

between 0 (inclusive) and 10 (exclusive).

To execute this check completely, we need to check that all index operands

are legal. You may have noticed that our prior example actually has two

index operands; we have to check both that tmp points to at least one

integer array of size 10, and that x is a valid index for such an array.

In general our algorithm for modifying LLVM code is this:

- Initialize the current type to be the type of the first operand.

- Initialize current operand to the first index operand.

- If possible, insert instructions to check if current operand is in bounds based on current type.

- Set current type to the next element type (e.g. if current type is *int[] the next type is int[]).

- If there are no more index operands, exit. Else, set the current operand to the next in the operand list and goto (3).

GEP Checking: A Walkthrough

In this section we'll walk through the above example in excruciating detail.

Feel free to skip ahead to the next section

if you're an expert in how getelementptr works and/or the above algorithm makes intuitive sense.

The main complicating part of the above algorithm is how to compute the next element type. Based on the possible types that GEP expects there are only a few cases to handle. Intuitively, each type represents a container in some way and "indexing" into it should get us the type contained by the outer one.

| Type | Next Element Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| t* | t | For pointers, the next type is the type being pointed to |

| [ size x t ] | t | For arrays, the next type is the array element type |

| < size x t > | t | Vectors, like arrays, have an element type |

| struct { f1, f2,...,fn } | fi | i is the index value; LLVM requires this is a compile time constant |

Checking the instruction:

%addr = getelementptr [10 x i32], [10 x i32]* %tmp, i64 0, i64 %x;

PointerSource = %tmp; CurrentType = [10 x i32]*; CurrentOp = i64 0; //Get the max offset for accessing %tmp. Since %tmp was generated with // %tmp = alloca [10 x i32] //We know that %tmp points to only 1 integer array NumElements = 1; InsertCheck(CurrentOp >= 0 && CurrentOp < NumElements); // (0 >= 0 && 0 < 1) //Our implementation will actually automatically omit this //check since it can be easily statically determined to be `true` CurrentType = NextElementType(CurrentType); //[10 x i32] CurrentOp = i32 %x; NumElements = 10 // retrieved from the type [10 x i32] InsertCheck(CurrentOp >= 0 && CurrentOp < NumElements); // (x >= 0 && x < 10) CurrentOp = <none>; //Done!

Pointer Sizes and Tracking Allocations

In the above examples, we could always tell how big our memory allocations

were since they were allocated with static sizes. int tmp[10] comprises two static allocations: 1) a single pointer-sized memory cell (to contain the local variable tmp); 2) a memory cell

containing 10 integers (the memory pointed to by tmp).

In many cases, the sizes of arrays may be difficult or impossible to determine at compile time. Consider the following snippet:

int foo(int x, y) { int tmp[x]; ... //init values in tmp return tmp[y]; }

In the corresponding LLVM code, the type of tmp is no longer a sized type;

it is just i32*. We can no longer use types to help us determine what

are and are not legal offsets. In this case, however, there is something

that we can do. LLVM uses alloca

instructions to allocate local variables. alloca takes an argument to

determine how many elements must be allocated. If we keep track of the

sizes of local allocations we can infer that the above code is safe if and only if:

0 <= y < x //we'll assume x > 0 here

In our implementation, we simply keep around a map from allocations to their sizes.

Additionally, we track heap allocations by scanning for function calls to malloc.

This allows us to calculate maximum pointer index values for GEP instructions

where the types are unsized. Unfortunately, this is rather imprecise since

it tracks exact value dependencies and doesn't keep track of other ways

a pointer may be passed to a GEP. For instance, spilling a value to memory

and then re-loading it will cause our analysis to lose track of the original

allocation.

Additionally, we run our transformation as a function pass so it doesn't track interprocedural allocations. The main reason for this limitation is that, even if we knew the original allocation size for all callers, we would have to modify the function signature to communicate legal index values from the caller. This seemed both out of scope for our current project and a potentially questionable design decision. Should a compiler pass be modifying the signatures of potentially every function?

Alternatively, one could implement a much more heavyweight dynamic checker in the style of Valgrind or this other CS 6120 project. These checkers keep track of all allocated pointers and aliases in a large run-time datastructure to ensure that no dereference is illegal. This is a different approach, focused less on static analysis and more on total safety but comes with much larger run-time overheads in both space and time.

Consequently, our pass is unable to improve the memory safety of this function:

int foo(int* x, int y) { return x[y]; }

We had hoped to use LLVM's alias analysis or copy propagation tools to increase the precision of allocation tracking. However, we couldn't get these to work; they were difficult to integrate and didn't seem to track pointer value propagation as we expected them to. LLVM's relatively new MemorySSA analysis seemed very promising, since their example code finds domination relationships between memory uses and definitions. This would allow us to, at least for some cases, track allocation size information transitively through pointer reads and writes. However, the implementation is less precise than the documentation lets on and does not find accurate enough relationships to identify the root allocation for any pointers in practice.

Bitcasting

Additionally, bitcast instructions complicate this process

even more, since they cause the "sizes" of memory allocations to

be interpreted differently.

%1 = alloca i32, i64 10 %2 = bitcast i32* %1 to i8*

Since 4 i8 values fit into one i32, the allocation of %2 represents a totally

different number of elements than %1 even though they represent the result of the

same allocation operation.

In the above code, a GEP that uses %1 can safely index into elements 0 to 9.

However, a GEP that uses %2 as the base can safely index into elements 0 to 31.

For any bitcast instruction that casts an allocation of known size, we convert

and track the size of the new value, using integer multiplication and division

to soundly approximate the maximum safe index. For typical bitcasts (e.g., char to int)

this will not lose precision; however LLVM does have arbitrary precision integers,

which could cause this estimate of allocation size to be an underestimate.

Soundness and Completeness

Often, when trying to ensure a safety property you'd like to show that your results are either sound or complete. In our case, soundness would imply that any LLVM program which uses no "type unsafe" features and is compiled with our pass executes no GEP instructions which would generate out-of-bounds pointers. Completeness, on the other hand, would imply that we can compile and execute all programs that never execute out-of-bounds accesses. In other words, completeness ensures that all safe programs should still be executable after our instrumentation.

Typically, you cannot achieve both soundness and completeness simultaneously; although, the use of code transformation to insert run-time checks does make this tractable for some problems. Our solution achieves only completeness and not soundness; we allow all programs to execute by skipping checks where we cannot determine the legal index bounds. A simple sound alternative would be to simply reject any programs that fit the above criteria; by placing an unconditional exit in front of any such GEP instruction we could ensure safety but would prevent some safe programs from executing.

A Note on Soundness

Soundness for our problem isn't really achievable without some assumptions about the behavior of LLVM programs oustide of the GEP instructions (or without a much more complex interprocedural analysis).

To highlight one of the reasons for this, consider the following LLVM program:

%1 = alloca [10 x i32] %2 = bitcast [10 x i32]* %1 to [11 x i32]* %3 = getelementptr [11 x i32], [11 x i32]* %2, i64 0, i64 %x

The above LLVM code is totally legal and will compile using standard LLVM tools. However, this example invalidates the assumption that our pass uses to ensure GEP safety.

To be clear, %1 is a pointer to an array of 10 32-bit integers,

but the next instruction copies that same pointer value into %2

while treating it as a pointer to 11 32-bit integers.

When our pass analyses %3 it will insert the following bounds

check for %x:

0 <= %x < 11

Executions where %x == 10 will cause memory safety violations.

We consider such behaviors outside the scope of this project

and assume that the LLVM types for the arguments to the GEP

instruction reflect accurate allocations of memory. This assumption

is what we mean by not using "type unsafe" features.

Evaluation

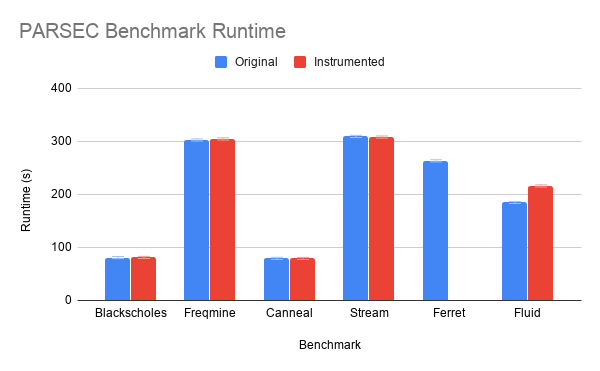

To evaluate the utility of our pass, we took a selection of PARSEC benchmarks and considered both: 1) How often we failed to determine the legal bounds for a pointer; and 2) How much run-time overhead we inccured with our dynamic checks. Furthermore, we ran a number of microbenchmarks to ensure that our pass was properly instrumenting code in the absence of the soundness problems that we mentioned above.

We chose benchmarks primarily by the ones that we could get

to compile most easily, so they may not be reflective of as

wide a range of behaviors as possible. We maintained the

same compiler flags used in the original suite, specifically

using the -O3 optimization flag. For an apples to apples comparison

the "Baseline" uses Clang to compile but does not run our transformation

pass. The "Instrumented" code is generated by running our pass after -O3 optimization but

does not run any further optimizations. Therefore, any overheads we find

should be considered upper bounds as optimization may remove some of

them or improve how they are calculated.

We ran the benchmarks a total of 10 times each and calculate both the average and standard deviation of execution time. These were executed on a Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-7700 CPU @ 3.60GHz, with 32GB of RAM and only one thread allocated per execution. The reported execution times are based off of the built-in PARSEC region of interest measures which only report execution of the hot loop and omit initialization and clean up times.

Evaluation: Precision

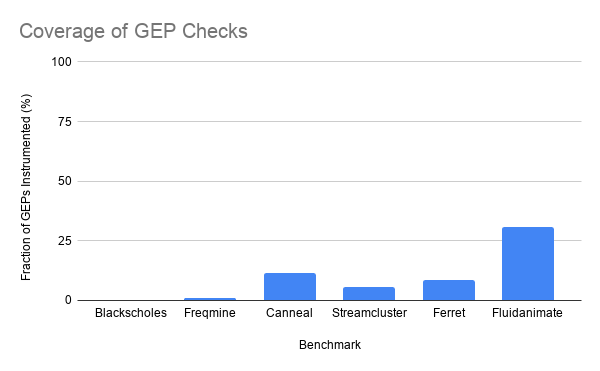

In all of the PARSEC programs we benchmarked, we failed to instrument most of the unsafe memory acceses. As you can see by the graph below, in the best case (Fluidanimate) we managed to instrument 30% of GEP instructions, while in the worst we added no run-time checks (Blackscholes).

Based on our manual observation of the compiled code and testing our instrumentation with microbenchmarks, we believe this lack of precision stems from two main sources:

- Pointers allocated outside function scope (arguments and global variables)

- Allocation information loss due to operations on pointer variables

As mentioned previously, the former is difficult to deal with as an IR compiler pass since a general solution would require modifying function signatures to pass allocation size information.

The latter problem stems primarily from three operations: load, store and getelementptr.

While complications arising from GEPs are straightforward to solve (since that's already an instruction

we're instrumenting already), without precise memory dependency and alias analyses,

we cannot track allocation sizes of pointers derived from other pointers.

The most common case we noticed, anecdotally,

were global pointers to data that were "malloced" at the beginning of the main function,

but accessed throughout the program.

For instance, take the Blackscholes benchmark, for which we instrumented no GEP instructions.

It has a global pointer to an array of floats called prices, whose size is determined during

the beginning of execution:

fptype *prices; ... main() { ... prices = (fptype*)malloc(numOptions*sizeof(fptype)); ... }

The above allocation translates to the following LLVM IR:

%46 = tail call noalias i8* @malloc(i64 %45) #9 store i8* %46, i8** bitcast (float** @prices to i8**), align 8

Our analysis determined that the run-time size of the memory pointed to

by %46 was given by the value %45.

However, %46 is not used as the argument to any GEP instruction, instead

later operations use a load to retrieve the array pointer from prices.

%179 = load float*, float** @prices, align 8 %180 = getelementptr inbounds float, float* %179, i64 %159

Since we are not running a memory dependency analysis we could

not determine that the size of the allocation pointed to by %179 was %45.

Often, these two problems combined, since prices may be accessed

outside the scope at which %45 is available and we therefore would need

to modify the program to communicate this allocation information (potentially

via an extra global variable).

Evaluation: Overhead

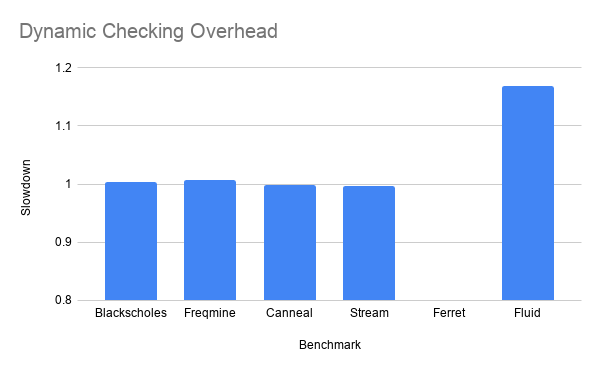

We measured run-time overhead in terms of wall clock time purely because it was the simplest thing to instrument and probably the most relevant bottom-line metric when inserting dynamic checks. In the following graph we report the average slowdown caused by our instrumentation (lower is better). At the end of this section is a graph reporting our base results (rather than the ratio) which reports the mean execution time for both configurations. Error bars on that graph represent one standard deviation.

In the case of the Ferret benchmark, our instrumentation caused the implementation to exit prematurely. Since the benchmark is quite large we did not have time to investigate why this was; it is possible that Ferret intentionally executes "unsafe" GEP instructions. Since our instrumentation did not cause bugs in any of the other implementations we find this to be a likely cause, but it does warrant further examination.

Interestingly, the instrumented Canneal and Streamcluster benchmarks run ever so slightly faster; however, this result is within the standard deviation and could also be influenced by effects covered in the first blog for this course. Without running any real statistics, it seems like the instrumentation only had a meaningful impact on the Fluidanimate benchmark. Somewhat unsurprisingly, this is also the benchmark for which we managed to instrument the most GEP instructions.

Intuitively, our instrumentation should add run-time overhead which scales with the number of GEPs and the number of times each of those GEPs are executed. It would have been interesting to determine how "hot" each GEP instruction was and drill down into where the overhead was coming from. That would have involved much more invasive profiling which we did not implement.