Loop-Level Automatic Vectorization

Introduction

Modern processors have support for SIMD instructions, which allow for efficient vector operations. We can leverage this feature to optimize loops that operate iteratively on arrays by changing operations that act on single array elements into vector operations that act on multiple array values in one instruction.

Consider the following loop of a vector-vector add:

# Assume a, b, and c represent array base addresses in memory such

# that the arrays do not overlap.

...

one: int = const 1;

vvadd_loop:

ai: int = add a i;

bi: int = add b i;

ci: int = add c i;

va: int = lw ai;

vb: int = lw bi;

vc: int = add va vb;

sw vc ci;

i: int = add i one;

done: bool = ge i size;

br done vvadd_done vvadd_loop;

Compare this with the following loop:

four: int = const 4;

vvadd_loop:

ai: int = add a i;

bi: int = add b i;

ci: int = add c i;

va: int = vload ai;

vb: int = vload bi;

vc: int = vadd va vb;

vstore vc ci;

i: int = add i four;

done: bool = ge i size;

br done vvadd_done vvadd_loop;

The second loop executes for a fourth the number of iterations of the first loop while behaving identically by using vload, vstore, and vadd that operate on four array elements at a time. This allows for i to be incremented by four each iteration instead of by one.

For this project, we designed and implemented automatic loop vectorization by converting serial operations on array elements to their vector counterparts. We build on Philip Bedoukian's work that brings vector instruction support into the Bril interpreter. We use his array implementation and the vector operations that he provides which operate on vectors of length four. We did not use his C++ dynamic library, and instead wrote a new dynamic library in Rust with a wider range of function calls as we were more familiar with the Rust specification. In addition, this choice proved to be a valuable learning opportunity.

Design Overview

To vectorize a loop, we must first detect loops, check whether they have dependencies that prevent vectorization, vectorize array operations, and deal with extraneous serial instructions.

Dominator Analysis

We need a dominator analysis to find loops, and so we implemented this dataflow analysis as follows:

Edge: Each out edge of a block consists of all blocks that dominate it, including itself Direction: Forward Initial Value: Set of all blocks Merge: Set intersection (or empty set if first block in program) Transfer: Current block unioned with in-edge

Loops

We first define a back edge as an edge from A to B where A and B are basic blocks and B dominates A. This is essentially the control flow edge that transitions from the end of the loop back to the beginning. As such, we define the loop as all blocks along the path from B to A, which we find using DFS.

Now that we are able to find a loop, it must have the following elements to be vectorizable:

- A branch statement (to exit the loop)

- e.g.,

br done exit loop_header;

- e.g.,

- A condition variable (boolean variable for the branch argument)

- e.g.,

done: bool = eq i size;

- e.g.,

- An induction variable that increases or decreases each iteration

- e.g.,

i: int = add i one;

- e.g.,

These are the minimum requirements for creating a loop that iterates a set number of times. To actually get these values, we need to enforce that there is only one branch statement in the loop. We do not handle loops with multiple branches in this project as it is much more complex to hadle vectorization for nested or loops where some statements run more iterations than other statements. We also restrict the induction variable, condition variable, and branch statement to be the last three instructions in the loop to enforce the same number of total iterations for all statements, which would not be the case if statements were allowed after the branch since those would be executed one less time than statements before the branch.

From these, we can find more information such as the variable that specifies the bound, which can be deduced from the arguments for the condition variable as one argument must be the induction variable, leaving the other to be the bound.

We now want to verify properties to ensure that this loop is indeed vertorizable. For example, we need to know that the bound variable is a constant and not something loaded from memory, or we won't be able to determine how many times the loop is executed. This requires us to know the latest definition of variables, which we get using a reaching definitions analysis. It is possible to find that statement walking backwards through the CFG, but we found using a dataflow analysis to be a much cleaner approach. Furthermore, we'd also like to know values of variables at different program points, such as the base pointers for array loads or stores, which we can get through a copy propagation analysis.

For both of those analyses, we found it to be very helpful to have information at the statement level instead of the block level. For example, in the block with the condition variable, it is possible that the bound is defined in that block before the condition variable statement and then again after the statement, and so if we only had the copy propagation values at the in and out edges of that block, we would not get the correct value the condition statement sees. We wanted to avoid iterating through blocks to make sure variables are not redefined, so we made each statement a block by adding trivial jumps and labels between statements, thereby getting finer-grained analyses.

Reaching Definitions

Edge: Each edge is a dictionary from variable names to their latest definition, or to None if multiple definitions reach that point. Direction: Forward Initial Value: Empty dictionary Merge: Unions the in-edge dictionaries if a variable (key) does not exist in both dictionaries, and set the varible's definition statement (value) to None if it exists in multiple dictionaries. Transfer: Starting with the merged in-edge (a dictionary from variable to definition) we set the value for every variable defined in the current block to that definition statement.

Copy Propagation

We used the copy propagation analysis already in the Bril repo.

Validity Checks

Now that we have reaching definitions and copy propagation per statement, we can check whether a loop is vectorizable.

The primary reason a loop is not vectorizable is due to flow-dependencies. A flow-dependency is when a variable uses information from the pervious iteration of a loop, such as when a value is loaded from an array position that was written to in the previous iteration of the loop. To detect this, we use the fact that indexing into an array is typically done by adding an offset to the base pointer of an array. We are able to find the variables representing array pointers by examing load and store instructions' arguments, and then we use information from our reaching definitions analysis to check whether those variables are computed each iteration as an addition of a constant and another variable.

Since our vector load/store instructions access four consecutive values, we also need to enforce that the non-constant variable is the induction variable, and also that the induction variable must increment or decrement by exactly 1 every iteration. This ensures that arrays are always accessed sequentially.

The number of iterations can be computed from the bound variable, the condition variable, and the initial value of the induction variable, and this number allows us to find array lengths since arrays are sequentially accessed per iteration. With the base array pointers and array lengths, we can now check that arrays do not overlap, which then proves that they cannot have flow-dependencies as each array location can only be accessed once in the duration of the loop.

To be able to convert singular addition operations to vector addition, we also check that operations on loaded values must only involve loop-invariant variables (i.e., variables that do not differ per iteration) so that those operations are not flow-dependent. We then check that stores only store variables that are either constant or are results from operations on loaded values (which we previously enforced to be flow-independent).

After we are confident that the array operations in a loop are vectorizable, we now need to convert the loop structure to its equivalent vectorized form.

Strip Mining

Since we are working with vector operations on four consecutive array elements, we "chunk" the sequence of loop iterations in blocks of four, which is known as strip mining.

Trivially, strip mining can be done by finding the statement that increments the induction variable and changing it from incrementing/decrementing 1 to incrementing/decrementing 4. All operations on array elements are changed to their vector counterparts, e.g., add would become vadd. This would work as long as the loop only included operations on arrays, but we found that to often not be the case.

For example, printing the i each iteration, where i is the induction variable, should still allow the loop to be vectorized as there are no flow-dependencies, but if we change the induction variable by four each iteration, that print statment will behave incorrectly as it would only print one out of four elements. To mitigate this, we do partial loop unrolling when strip mining.

To achieve this, we go through the loop and find non-array instructions and keep track of them. Then, we append them to the end of the loop (before the condition and branch statements) and also a copy of the induction variable increment/decrement. We do this insertion three times total.

Example loop snippit before strip mining and partial unrolling:

loop:

print i;

ci: int = add c i;

v: int = lw ci;

i: int = add i inc;

done: bool = eq i size;

br done exit loop;

After strip mining and partial unrolling:

loop:

print i;

ci: int = add c i;

v: int = vload ci;

i: int = add i inc;

print i;

i: int = add i inc;

print i;

i: int = add i inc;

print i;

i: int = add i inc;

done: bool = eq i size;

br done exit loop;

With this method, array operations are allowed to be vectorized while preserving serial instructions because serial instructions are unrolled into four copies, where each copy operates with a different induction variable value. This loop also increments the induction variable by four every iteration which preserves the performance increase from reduced branch overhead.

In terms of implementation, we found it much easier to first coalesce the loop into one big block before running the strip mine algorithm because we could treat this sequence of instructions as one array instead of having to worry about jumps and label renaming from inserting new blocks. Aggregating all the blocks of this loop was possible because we previously enforced that there can be exactly one branch instruction located at the end of the loop.

Up to here, we have been operating on the assumption that array sizes are divisible by the vector size---four. To account for arrays not divisible by four, we append a copy of this loop (without any optimizations) to a block that follows the main optimized loop. This serially executes the remaining loop iteration which allows us to maintain correctness. This also means that we need to floor the loop bound of the vectorized loop to the nearest multiple of four but keep the original bound for the serial loop that follows.

Rust Dynamic Library with Foreign Function Interface

In order to more accurately measure the performance impact of automatic vectorization, we design a dynamically linked library in Rust with a foreign function interface. We use the Rust crate for SIMD that targets the x86 platform to utilize SIMD intrinsics to support vector-add, vector-multiply, and vector-subtract. These functions are called in the dispatch loop of the interpreter for the corresponding vectorized instructions.

Consider the Rust function for vectorized addition.

#Requires data_a, data_b, and data_c to point to arrays

# of 32-bit integers of length 4.

#Adds the arrays pointed to by data_a and data_b element-wise

# and store in array pointed to be data_c.

#[no_mangle]

pub fn vadd(data_a: *const i32, data_b: *const i32, data_c: *mut i32) {

unsafe {

let a = _mm_load_si128(mem_a);

let b = _mm_load_si128(mem_b);

let c = _mm_add_epi32(a, b);

_mm_store_si128(mem_c, c)

}

}

The Rust crate for SIMD is currently required to be wrapped in an unsafe block. This is because it is the programmer's responsibility to ensure that the CPU the program is running on supports the function being called. For example, it is unsafe to call an AVX2 function on a CPU that does not actually support AVX2. (AVX2 is an extension to the x86 ISA that supports SIMD operations).

In order to justify these unsafe blocks, we used the #cfg attribute when compiling. This allows you to dynamically detect this CPU feature, and provide a fallback implementation in the case the CPU does not support SIMD operations. The processor we used for evaluation supported AVX2, so we did not need a fallback implementation for evaluation.

Consider the corresponding invocation of this Rust function in the interpreter for vector add.

case "vadd": {

let vecA = getVec(instr, env, 0);

let vecB = getVec(instr, env, 1);

let vecC = new Int32Array(fixedVecSize);

vadd(vecA, vecB, vecC);

env.set(instr.dest, vecC);

return NEXT;

}

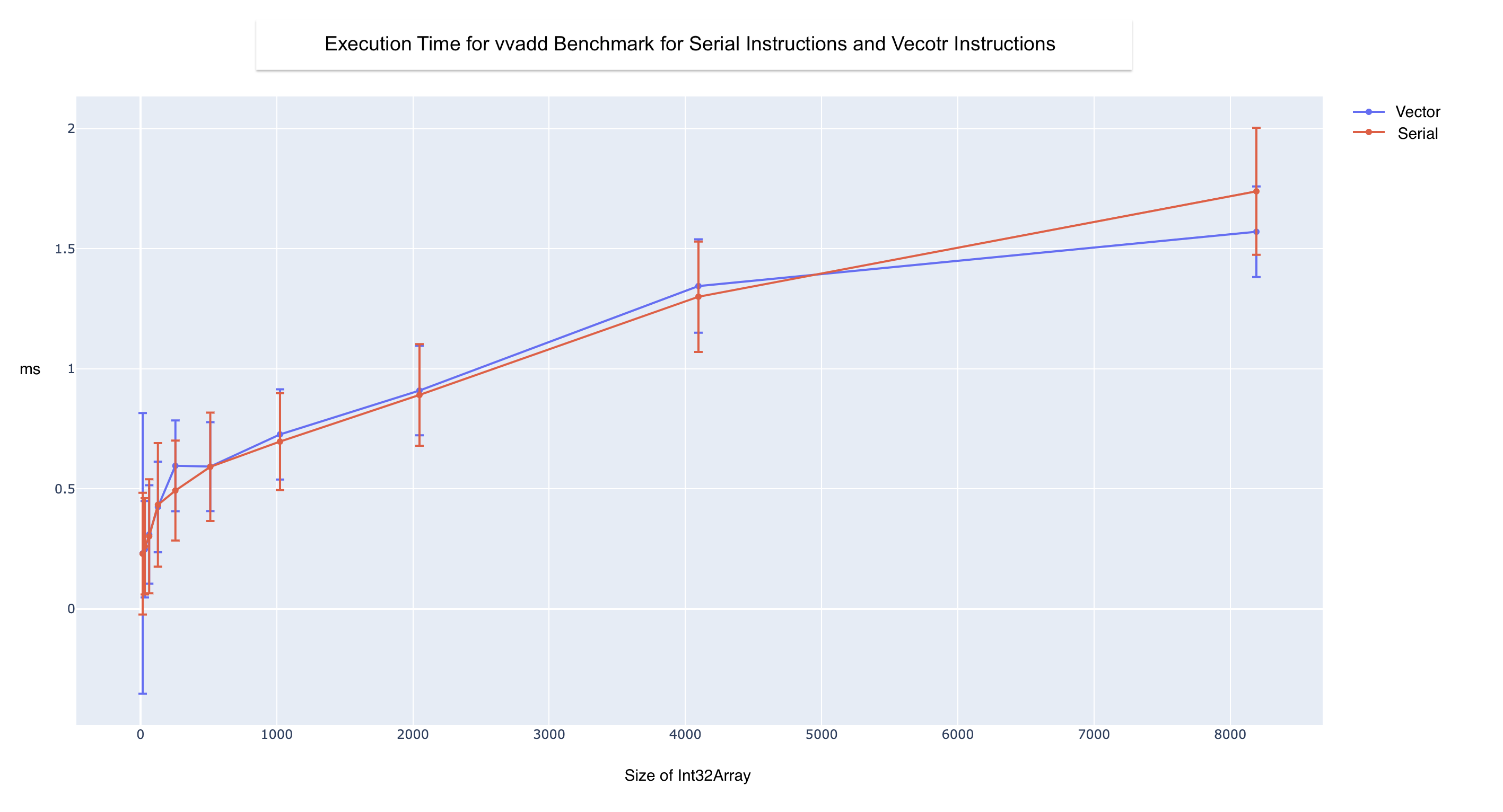

These external calls add potentially significant overhead to the execution. We quantify this overhead to more accurately evaluate execution time in the interpreter. We run a vvadd benchmark, documented below, varying array sizes of (128, 1024, 2048, 4196, 8192). We run 10 iterations of each configuration and average the execution time between them. We then compare execution time with and without calls to the Rust library. We find there is a 16% overhead for making Rust calls. While we predict this will be offset for especially large arrays, we decided to add Rust calls for serialized instructions as well to isolate the vectorized instructions as a variable in our experiment from the Rust call overhead variable.

In addition, note the loads and stores that accompany the vectorized add instruction. The vadd function implements c[i] = a[i] + b[i]. However, this line translated to Bril IR would look like the code below.

va: vector = vload ai;

vb: vector = vload bi;

vc: vector = vadd va vb;

vstore vc ci;

Ideally, these instructions would be in separate functions in our Rust library with separate invocations in the interpreter. However, TypeScript does not have a copmatible type for __m128i, which represents a 128-bit SIMD register. In order to separate the vadd from vload and vstore, we would either need to return a __m128i, or invoke additional functions in the Rust SIMD crate to unpack this value into 4 32-bit integers. Without a compatible type for __m128i, we did find a way to write a signature such that we could accept or return a __m128i from a single vector add. For the latter, adding functions to unpack integers adds potentially significant overhead every time we pass vectors between TypeScript and Rust. Therefore, we group these as a unit to more accurately mimic SIMD operations, as well as make vstore and vload effectively noops in the interpreter. This is valid as our implementation of automatic vectorization ensures each vload-vload-vstore is accompanied by some vector operation.

Evaluation

Correctness

In order to verify correctness, we chose self-verifying programs such that execution of the program proves the program computed the same value, and thus is correct in terms of inputs/outputs. These programs include vector-vector add, vector-vector multiply, and vector-vector subtract. In addition, we tested programs with combinations of these operations, as well as programs with dependencies to ensure we only conservatively unroll. Consider the following loop.

a[i] = mul sa[i] a[i]

b[i] = mul sb[i] b[i]

c[i] = add a[i] b[i]

In this case, while there are dependencies within the loop body, there are no dependencies between iterations of the loop. Therefore, we expect this operation will be vectorized.

We also enforced many constraints for what kinds of loops can be optimized, but we believe that it does not significantly impact expressivity. The loop format we described is most similar to a do-while loop where the loop condition is checked at the very end, but it is simple to compile regular while loops, do-while loops, and for loops from a higher level language into this Bril IR loop format using slight modifications to the loop bounds and conditions.

Performance

Determining how to measure the impact of this optimization was challenging as the primary benefit comes from special instructions in the SIMD instruction set that can operate on multiple data points in parallel.

One option is to implement 4 add operations in the interpreter's dispatch loop for vadd, 4 sub operations for vsub, etc. While this would not affect program correctness, it does not attempt to mimic SIMD registers that perform a SIMD operation in the processor. Therefore, it is likely to mispredict realistic speedup by naively ignoring external factors. In addition, the performance benefit seen under this approach would likely only reflect the decrease in number of instructions, rather the specifically the instrinsics of the SIMD instructions.

A second option is to use SIMD instructions in x86 with SIMD intrinsics. This approach involves execution of SIMD instructions that ideally much more closely mirror behvaior of SIMD operations. We modeled these SIMD operations this way for this reason using the aforementioned Rust dynamic library.

To evaluate our implementation, we run vvadd benchmarks. We run each benchmark on arrays of varying sizes (16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192). We initially ran 5 iterations per array size per benchmark, but noticed the execution times significantly decreased after each iteration. This is likely due to the CPU warming up, caching, and better branch prediction after each iteration. Therefore, we decided to increase this number to 25, after which the difference in execution times for sequential runs was less than 0.01 ms.

We ran these benchmarks and calculated the standard error bars by computing the standard deviation for each iteration for a given array size.

While the Rust SIMD calls do not appear to have a performance improvement as expected, there are a couple points to note. Some factors that could contribute to the performance impact could be communication costs and coupling of loads and stores with vectorized operations.

Communication Costs

The cost of the Rust calls likely dimishes the visible improvement. While we tried to mimize this by writing functions for serial operations as well in Rust, it inaccurately emphasizes the number of instructions as we artificially add a scalar overhead to them.

In addition, the calls from TypeScript to the Rust FFI are opaque and it is unclear how exactly they are made. It is also unclear how the arguments are passed in to the function, and what the associated costs are. Therefore, it is possible that some of the variance in the results can be attributed to the variance of these calls.

A next step to better isolate these vectorized instructions from the rust call overhead would be to write the entire interpreter in Rust, or some other language, and execute the SIMD instructions inline without function calls.

Coupling of Loads and Stores

As mentioned in the Rust FFI section above, the Rust functions that are invoked for a vector-add are coupled with vload and vstore as TypeScript does not have a corresponding type for __m128i. Therefore, it is possible that there are extra vloads and vstores performed for the vectorized programs. This would also diminish the potential performance impact.

To isolate each operation in Bril, we would need to write the interpreter in a language that has types compatible with 128-bit packed integers. This would enable the program to return the value from a vector load in the Dynamic Library to the interpreter. Similarly, we could then pass these 128-bit packed integers back to the Dynamic Library for the vectorized arithmetic operations.

Challenges

The two biggest challenges we faced were finding flow-dependencies and linking our Rust library. Since Bril is an IR, we do not have while, do-while, or for loops which are clearly defined and have easily identifiable loop guards. In Bril, we have to use analyses to find those loops and then check for dependencies. Incorporating calls to our Rust library also difficult because we had to translate values between Rust and Typescript, and building the library itself was challenging because the SIMD crate (Rust package) was unsafe and frequently resulted in segfaults.

Working with Python also proved somewhat difficult due to the lack of types.

Conclusion

We were able to correctly implement automatic vectorization in the Bril interpreter along with a dynamic library in Rust. However, we were not able to obtain a reliable execution speedup of these instructions due to the variance of FFI calls, coupling of loads and stores in our library functions, and extraneous cache factors.

In this work, automatic vectorization was implemented for Bril. A next step would be to reduce loop restrictions such as by allowing an arbitrary number of branch instructions to exist in a loop. This will be possible with a smart analysis on how many times the code between each branch instruction is executed. We can also eliniminate the overhead caused by calls to Rust by rewriting the Bril interpreter in Rust for a more accurate performance analysis.