Complexity Minimizer

The goal of this project is to transform a subset of recursive programs into their iterative counterparts.

Motivation

Execution time of a program is important. As a metric, execution time is relevant not just for saving loads of money from unnecessary compute, but is also relevant in terms of functionality. At the limit, writing faster programs can enable us to solve larger problems that require massive computational work in a tangible amount of time. Compilers can make a given program run faster. Often, we tend to look at classic compiler optimizations as a way to iteratively speed up a given program.

However, the scope of the optimization pass model is limited, especially when the program is algorithmically inefficient. If we are able to transform programs with unnecessarily $O(n)$ space cost into $O(1)$ space cost, or programs with $O(2^n)$ runtime into programs with $O(n)$ runtime, why couldn't a compiler?

One of the challenges of this idea is the notion of an algorithm. As humans, we can read the program, determine the task, and write a better program given the necessary computation. However, most compilers do not have a notion of the "goal" of a program. Similar questions arise in program synthesis when determining the "specification" of a program.

Computing the _n_th Fibonacci number can be done in an recursive fashion with an $O(2^n)$ time complexity or in a iterative fashion for $O(n)$. However, there is no compiler optimization that can produce the performance of the iterative algorithm when given the recursive one, so we attempt to make a generalizable optimization pass that can change similar recursive programs to their iterative counterparts.

Approach

In order to scope our project to tangible action items, we separated our idea into smaller milestones.

V0. Transform a recursive Fibonacci program into an iterative program

V1. Transform a recursive program with an arbitrary combination of elements on return (e.g., Fibonacci was f(n-1) + f(n-2))

V2. Expand scope of input set of valid programs to two-dimensional DP programs

A First Program

Before digging in to any code, we spent time thinking deeply about recursive DP programs and their iterative counterparts.

- What are the distinguishing parts of the recursive implementation that can give rise to an equivalent iterative program?

- Which parts of these recursive functions is the similar across them such that we can generalize?

- How do we know these are equivalent?

We decided to implement this at the LLVM IR level so that our optimization would be source-language-independent.

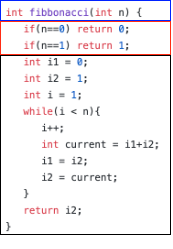

When considering iterative Fibonacci, there are two main parts: the base cases and the iteration. The base cases consist of returning 0 or 1 when n is 0 or 1 respectively, and the iteration part entails a while loop with an induction variable that iterates from where the base cases end to the desired n (i.e., from 2 to n becase the last base case is Fibonacci 1).

Information Collection

Given a recursive function, we found that this set of information was sufficient for generating a iterative version of that function.

- Base Cases

- Loop induction variable and its bounds

- How these recursive calls are combined (i.e., Fibonacci adds the results from the f(n-1) and f(n-2) together)

- The offset from the induction variable in the recursive calls (i.e., (n-1), (n-3), etc.)

In the case of Fibonacci, we demonstrate how an iterative versin of the program can be created using only the information above. We use C code here for better readability, but our implementation generates this in LLVM IR.

int fibbonacci(int n) {

// Base cases

if(n==0) return 0;

if(n==1) return 1;

// i1 and i2 store offset results

// i1 is Fibonacci(i-1), an offset of 1

// i2 is Fibonacci(i-2), an offset of 2

int i1 = 0;

int i2 = 1;

// i is the loop induction variable, bounded from 2 to n

int i = 2;

// Iteration part

while(i <= n){

i++;

// the combination instruction (Fibonacci only has one, but there can be multiple)

int current = i1+i2;

i1 = i2;

i2 = current;

}

return i2;

}

Information collection posed many challenges due to the low-level nature of LLVM IR, and desire to generalize our solution.

Finding the Base Cases

To more formally define the term base cases, we required base cases to be comparisons with the input argument to the function, found at the top of a program, that resulted in returning a value within the body guarded by the comparison.

While humans have no trouble deciphering the base case given a program, it is much more challenging to find them when sifting through LLVM IR. We used an ad-hoc approach where we found the constant return values and then walked up the CFG to find the conditional statements that would have led to those constant outputs. From the condition instruction we extracted the function argument that would have led to that constant to be returned, and we end up with a list of argument-return pairs, which sufficiently describes the base cases of the function.

Doing this better would involve abstract interpretation. For a particular function argument, it could trigger a recursive call or it could not. With abstract interpretation, we could find all values of the argument such that the basic blocks with recursive function calls are not traversed. Those would be the base cases.

Finding the Loop Induction Variable

For this project, we simply initialized the induction variable at the largest base case argument and incremented until it reached the function call's argument.

Finding the Instructions that Combine the Recursive Calls

We keep a running list of all recursive call instructions. For all instructions in the recursive function that use the result of a recursive call as an operand, we clone them and add the clone to a list of dependents as they depend on the recursive calls. We clone instructions here so we can delete all instructions in the recursive function and insert our own.

Finding Recursive Call Offsets

For each recursive call that we find, we look at the call argument and assert that it is a constant offset from the original function argument---i.e., of the form $(n-c)$ where $n$ is the original function argument and $c$ is a constant. We remember that $c$.

Creating a Model for Iterative Programs to use Collected Information

Once we have the information from the recursive program, we need to find a model such that given this information, can generate an iterative program. Instead of writing a single transformation function $LLVM_Pass$(Input Recursive Program) = Output Iterative Program, we break down the programs according to a layout.

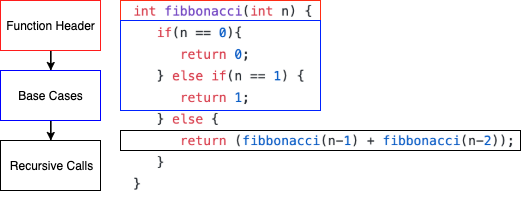

Consider the layout of recursive and iterative Fibonacci programs below.

Here, we separate the base cases from the recursive calls in order to know which set of instructions will need to be in a loop, and which set will only need to be called once. It is important to note that in the black box, you can have any set of instructions to combine the recursive calls.

Consider the layout of the iterative version of the same program below.

Note: We keep the function header the same in order to more easily swap out invocations to Fibonacci outside the function with our generated function.

New Code Generation

To minimize changes to the overall code structure, we delete all blocks and instructions inside the original recursive function and insert our new instructions.

First we add all the base case conditionals. Next, we declare and initialize all the values we need for iteration and the incrementing iterator. After that, we create the while loop and clone in the instructions dependent on the original recursive calls (e.g., the add instruction in fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)). Lastly, we add a return statement after the while loop to finish the function.

Our code for the LLVM pass is available here.

Evaluation

Correctness

In order to evaluate correctness, we look at the programs generated for a set of benchmarks that we created to test the generalizability of our pass.

Function equivalence is an undecidable problem, as that would solve the halting problem. Therefore, to approximately validate our generated programs are correct, we test the bases cases, and a few arguments for the iterative case.

We randomly generating a few integers between 2 and 47 , and 47 is the largest Fibonacci number that still fits in a 32-bit integer.

A next step to improve correctness checking would be to utilize randomized testing, but instead, determine the space of valid inputs from the input program itself.

Performance

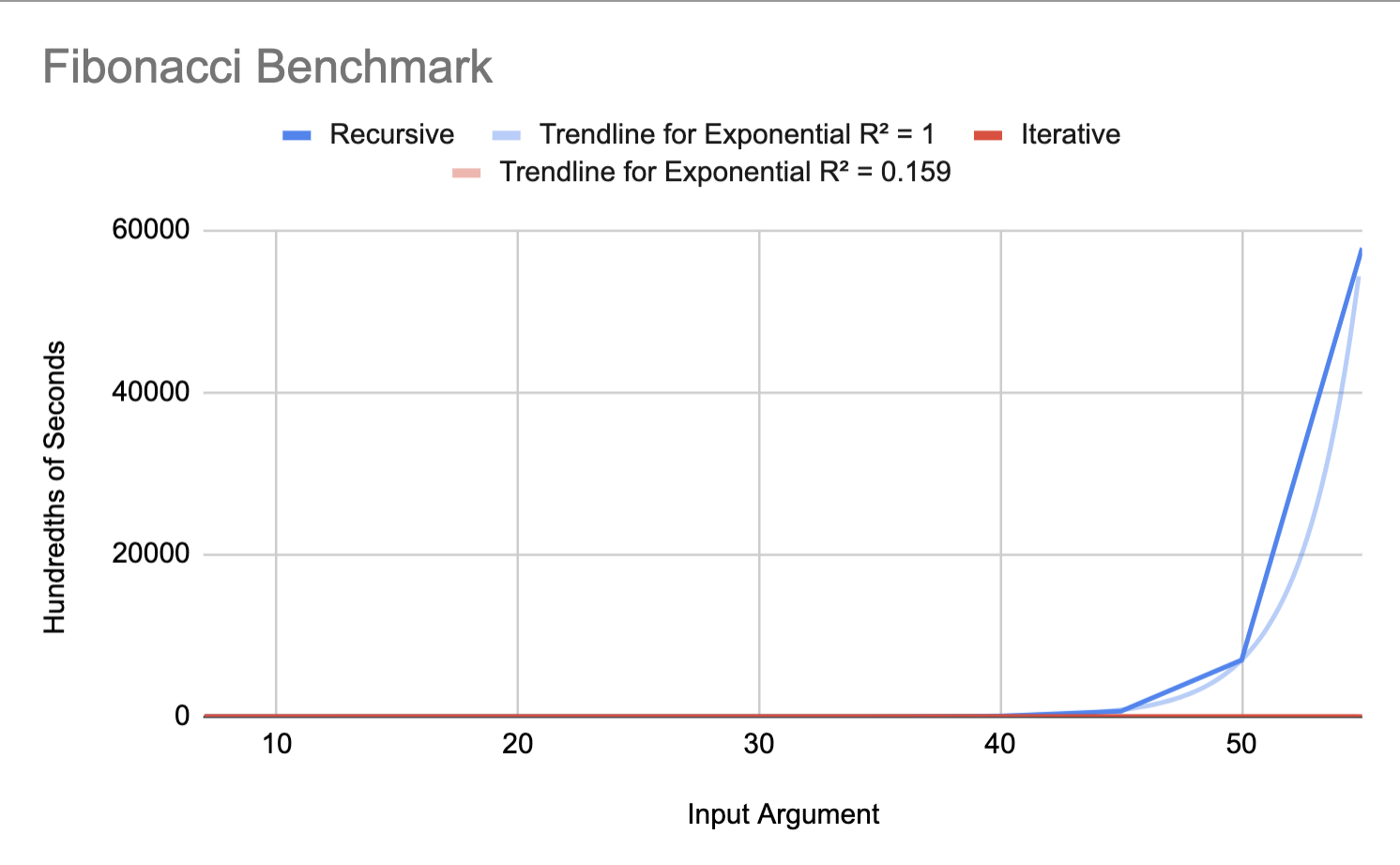

To measure performance, we ran derivatives of the Fibonacci program. We compare the execution time of the recursive program to the execution time of the iterative program.

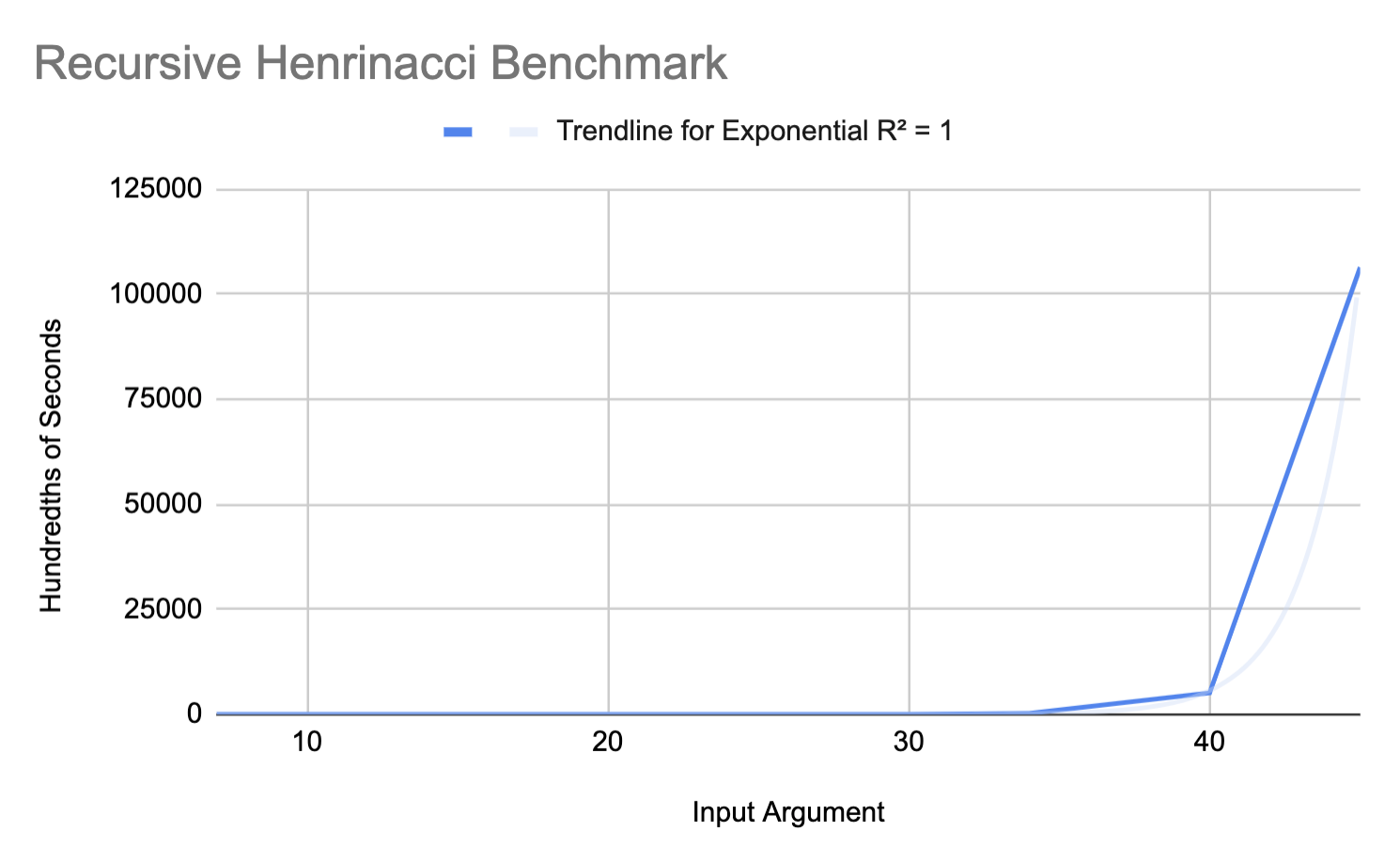

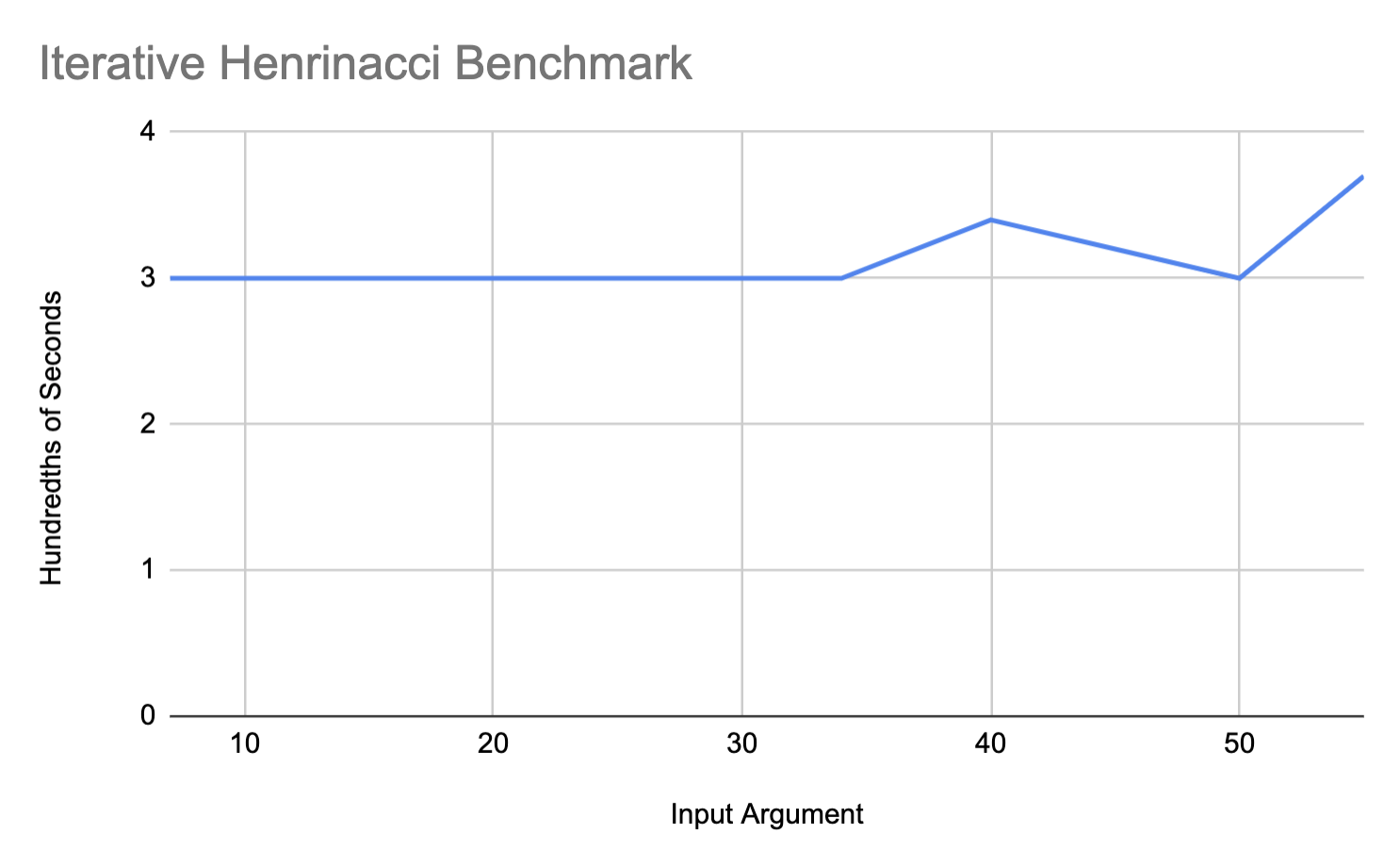

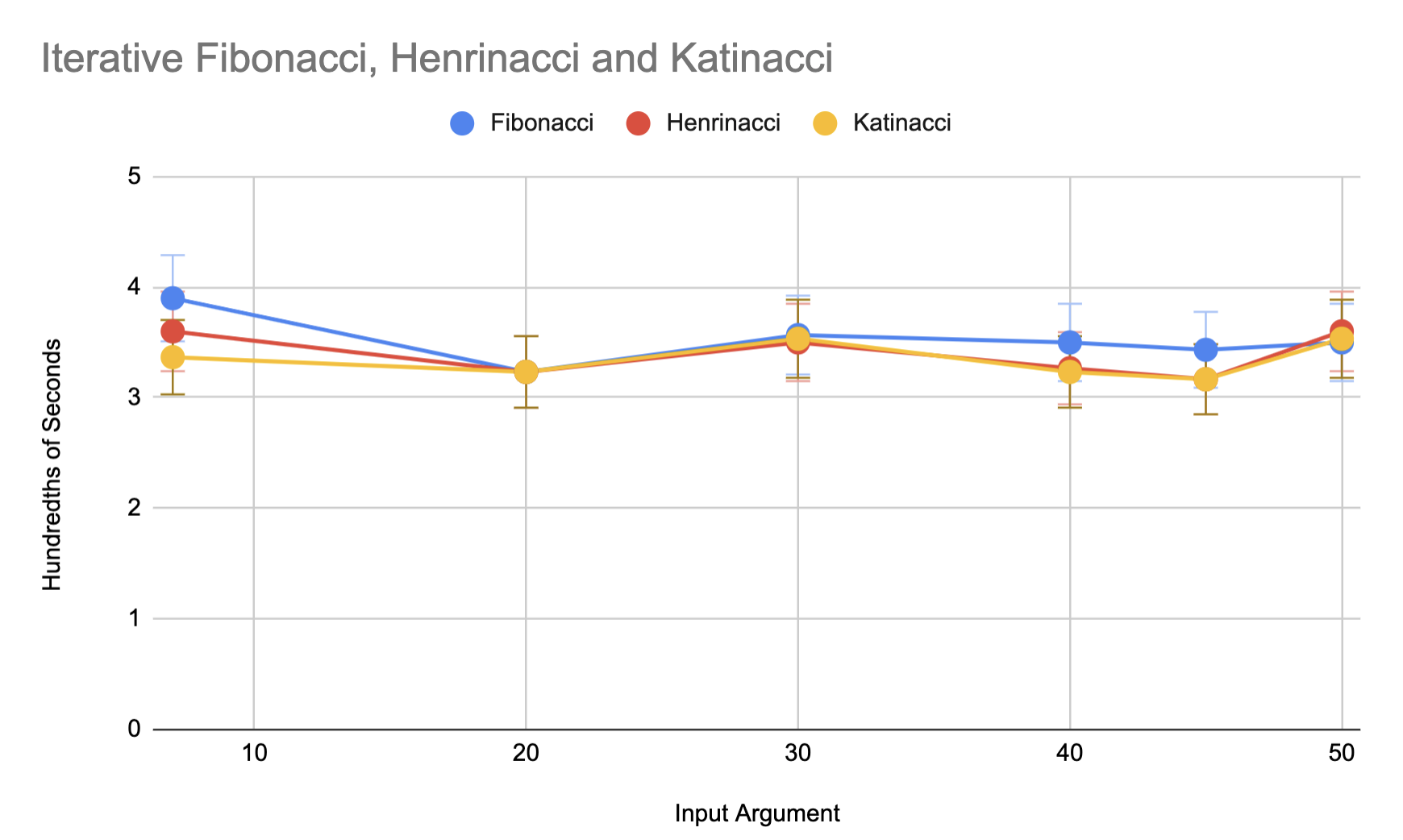

Here are the results of running the Fibonacci benchmark shown above. We see that the recursive benchmark follows an $O(2^n)$ execution time trendline as expected. We also see the iterative benchmark's trendline is very linear. By the data, the iterative trendline only varies between 3 and 3.5 hundredths of milliseconds between inputs 7 and 55. This is quite small. One reason this may be is that increasing n by 1 in the iterative benchmark, likely only increasing the number of add instructions by 1.

When interpreting these results, we considered the difference between these two programs. Consider the call tree for recursive Fibonacci. As $n \longrightarrow \infty$, the number of calls in the call tree grow by $O(2^n)$.

In addition to the redundant computation, the recursive Fibonacci program takes up more space, as it is not tail-recursive, and therefore requires many more stack frames for each computation.

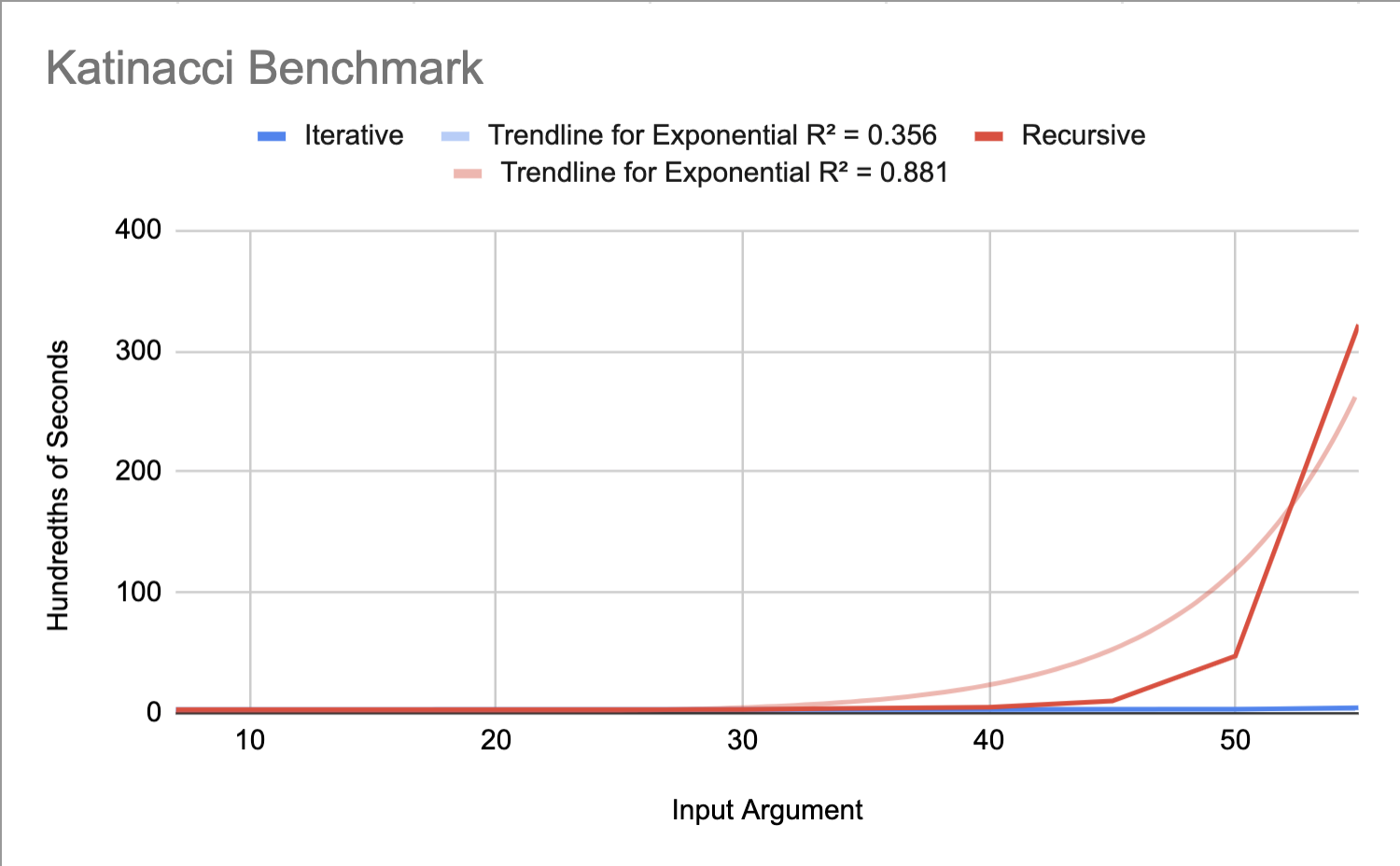

Next consider Katinacci, a derivative of Fibonacci, we created, with the recurrence: $$k(n) = k(n-1) + k(n-3)$$

Katinacci was designed to test recurrences with offsets that were not adjacent. We noticed that Katinacci does not follow the exponential trendline quite as closely as the rest of the benchmarks. One reason this may be, is that it approaches a base case much more quickly than the other benchmarks. Therefore, Katinacci may be a little bit lower on the graph than the exponential trendline, as shown.

Finally, Henrinacci, another derivative of Fibonacci we created, with the recurrence: $$h(n) = h(n-1) + h(n-2) + h(n-3)$$

We see the recursive cases of these benchmarks follow the exponential trendline, while the iterative benchmarks look much more linear. The data from the iterative benchmarks cover smaller amounts of time, and therefore, appear to be more influenced by noise. We run another set of benchmarks on the iterative versions of each of our benchmarks, 3 times per input argument, and plot the results below. Despite increasing the number of runs per benchmark, the error bars indicate there is minimal statistically significant difference between input arguments. Since these benchmarks were run together per input argument, it is likely noise from other processes is the reason the benchmarks vary similarly.

While these benchmarks are challenging to compare side-by-side for the iterative cases, it is clear that the iterative cases take much less time than their recursive counterparts. To achieve more precise results for the iterative benchmarks, it may be possible to run these benchmarks on larger input arguments and modify the program to return larger than 32-bit integer results.

Discussion

We have hit our V0 goal of generating an iterative Fibonacci from a recursive one. We have also satisfied our V1 goal of generalizing our implementation to recursive functions with any number of recursive calls with arbitrary constant offsets.

Our results show that we have successfully reduced the original functions' time complexities from exponential to linear.

We were not able to satisfy our V2 goals as they were too technically challenging. They would require analyzing a program and then procedurally generating a multidimentional array structure to iterate through, which we found difficult to do in LLVM IR.

Next Steps

We are currently using an iterator that always increments by 1. This is not optimal when the recursion contains large holes as we do not need all the values from the bases cases until $n$, such as $$f(n) = f(n-13) + f(n-17)$$ Instead, we need to somehow calculate the minimum number of computations. This can be done by "hopping backwards" from the desired $n$, where the hops are the offsets (in this case, 13 and 17). This then finds the minimum number of values, and also means that the induction variable needs to increase by values other than 1.

We have also only been considering functions with only 1 argument. The same principles should apply when extrapolating this algorithm to functions with multiple arguments.

There is also no reason this pass needs to work only with integers. However, implementing this pass for functions with something like string arguments becomes difficult as strings require memory accesses which introduces pointer analysis and much complexity.

This seems like a very powerful optimization pass if implemented in full. Many coding challenge questions involve dynamic programming, and having a compiler that can optimize a naïve recursive solution into a iterative version seems desirable in all circumstances.

One thing that doesn't seem feasible is handing non-constant recursive call offsets (e.g., f(n) = f(f(n-1)), or recursive calls that are not unidirectional (e.g., f(n) = f(n+3) + f(-n*2)) even if they are valid programs due to their base cases.

Primary Challenges

The primary challenge was using LLVM. The documentation is there but it is highly technical and it required a broad understanding of LLVM before things started "clicking". For example, we had immense difficulty with LLVM contexts (which were required for IRBuilder and basic block creation). Mix-and-matching LLVM contexts results in mysterious segfaults and correct usage was not obvious due to lack of examples.

It was also difficult to store and replay the instructions dependent on the recursive calls due to messy pointer management, specifically when setting the Use objects of those instructions to point at the new values we operate on for the iterative version.

Code generation was also on the more tedious side as we were writing LLVM IR. This was fine for our 1D functions, but for 2+D functions it seems like a better approach to generate higher level source code (such as C++ code) that implements our iterative function and then use Clang to compile it down to LLVM IR which we would then link in. This allows us to write code for complex things like multi-dimensional arrays in a higher-level language instead of LLVM IR.