Programs and functions

While using MATLAB as a fancy calculator has its own advantages, it is also possible to use MATLAB as a programming language and to develop with it significant programs with considerable ease.

Files that end with .m are recognized as MATLAB programs (or functions) and can be executed in MATLAB by typing their name. For example, the text below is kept in a file plotlog.m

% plot log(x) versus x

x = linspace(1,10);

y = log(x);

plot(x,y)

The first line is a comment in the file that tells us what the program is all about (it is plotting the log function) In the first line we assign to the array x 100 points between 1 and 10. The second line computes the log(x) (natural logarithm) and the third line plots x versus y.

To execute this program all we need to do is to type the name of the file (plotlog) in MATLAB main console and the complete file will be executed.

Note that the directory where the *.m file is located must be included in the list of directories that MATLAB searches for such a program. Choose from “File” the “set path” option to add the directory to the current list. Alternatively, you can use the “cd” command to switch to the directory where the file is located.

Of course, the program as described above cannot receive arguments directly. It is possible to simulate parameter passing by initializing the .m file’s relevant internal variables (if any) before calling it, but this requires knowing more about the file than we want. The method below, using functions, is much better.

MATLAB allows the use of functions. Similarly to the program mentioned above they are always stored in .m files. The name of the function as called from the main window of MATLAB must be the same as the name of the file.

Consider an example of a function to compute the volume of a sphere, given the sphere radius

The syntax of the first line in a function is:

function [output] = function_name(input parameters)

----------------------------------------------------

function [volume] = volsph(r)

% volsph - a function to compute the volume of a sphere

% r is the radius (input), "volume" the volume (output)

% THE COMMENTS THAT COME IMMEDIATELY

% AFTER THE “function …” LINE

% ARE PRINTED WHEN TYPING “help function_name”

%

volume = (4.*pi/3.)*(r.^3);

----------------------------------------------

The name of the file is volsph.m

Here is an example of a use of the function in the main window of MATLAB:

>> volsph(5)

ans =

523.5988

Or, computing several volumes in one call:

>> r = [1,2,3,4,5];

>> vol = volsph(r);

>> vol

vol =

4.1888 33.5103 113.0973 268.0826 523.5988

Input and output

Here is an example of getting input directly from the main window:

>> a = input(' type in something \n ')

type in something

1

a =

1

The command a “ a= input(' type in something \n ') “ echoes to the screen the expression enclosed within the quotes ‘…’; the “\n” means starting a new line. Whatever is typed as a response is placed as the value of the “a”.

Of course, for getting in a lot of data we need to be able to read from a file. Here is a quick introduction to fscanf.

The text below is a part of a file (name 1bii.ca) that includes a series of points (x,y,z coordinates).

19.842

31.925 54.112

19.411

33.862 50.859

16.466

35.443 48.997

15.760

36.986 45.649

13.746

39.450 43.589

13.651

38.210 39.954

11.896

39.631 36.876

10.937

37.345 33.994

10.155

39.213 30.789

8.895

37.761 27.498

8.413

39.265 24.006

7.029

37.077 21.245

6.677

38.387 17.687

3.525

37.515 15.771

3.652

38.703 12.134

0.328

36.961 11.420

-1.414

38.234 14.565

-0.102

41.838 15.052

2.488

43.625 17.254

4.463

41.562 19.795

2.880

40.154 22.875

4.916

41.493 25.783

4.818

40.384 29.440

6.616

41.042 32.712

6.452

38.720 35.712

7.948

39.620 39.140

8.937

37.066 41.830

10.219

37.016 45.410

11.626

33.484 45.836

9.088

30.957 44.396

6.279

33.493 44.791

.

.

.

We want to read all the points into three arrays (x, y, and z with the Cartesian coordinates) without knowing in advance the length of the file. This is (relatively) simply done with fscanf and fopen. Below is a small function to do that, preceded by the calling

line from the main window

MATLAB console

[x1,y1,z1] = get_points('1bii.ca'); % get the

Cartesian coordinates from 1bii.ca into x1,y1,z1

And the function…

function [x,y,z] = get_points(filename)

% read set of points from a file (each line x,y,z coordinates)

% and return the results in 3 arrays x,y, and z

%

fid = fopen(filename);

crd = fscanf(fid,'%f');

dim = length(crd);

x = crd(1:3:dim-2);

y = crd(2:3:dim-1);

z = crd(3:3:dim);

Note that fscanf is reading to the end of the file (unless being instructed otherwise; see help fscanf for more details). The coordinates are read as one very long vector in which the x, y, and z coordinates are stored as x1,y1,z1,x2,y2,z2,… By manipulation of the indices we create the three desired arrays.

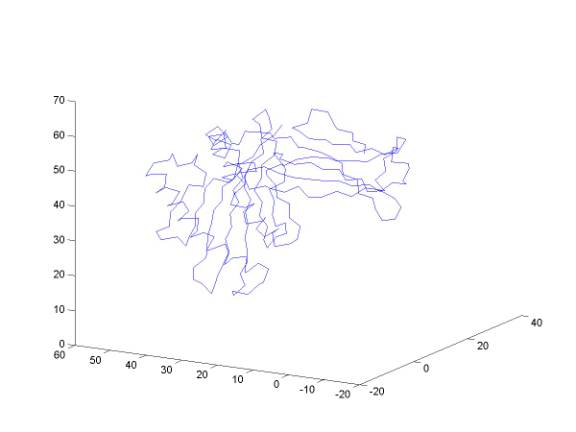

The points represent the shape of a protein. The protein is a one-dimensional chain and each point corresponds to the CA of an amino acid. Connecting them by a curve as embedded in 3D is done by the simple command (in the console of MATLAB):

plot3(x1,y1,z1)

Can you identify secondary structure elements?

Plotting protein structures:

The protein data bank is at www.rcsb.org (Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics). A gentle introduction to protein structures can be found in:

Carl Branden & John Tooze, “Introduction to Protein Structure”, Garland Publishing NY 1991

PDB files are formatted and include more information that we need or want during this class.

The files open with comments, references and classifications of experimental techniques and structural features. We will be interested in the coordinates. These are lines that start with the keyword ATOM.

Here are typical ATOM entries:

ATOM 1 N VAL 1 -4.095 14.896 13.982 1.00 17.14 1MBC 88ATOM 2 CA VAL 1 -3.483 15.451 15.217 1.00 17.16 1MBC 89ATOM 3 C VAL 1 -2.562 14.402 15.817 1.00 15.95 1MBC 90ATOM 4 O VAL 1 -2.966 13.230 15.884 1.00 17.17 1MBC 91ATOM 5 CB VAL 1 -4.592 15.944 16.184 1.00 18.07 1MBC 92ATOM 6 CG1 VAL 1 -4.213 17.270 16.885 1.00 17.77 1MBC 93ATOM 7 CG2 VAL 1 -5.962 16.191 15.584 1.00 19.17 1MBC 94ATOM 8 N LEU 2 -1.328 14.772 16.218 1.00 13.50 1MBC 95ATOM 9 CA LEU 2 -0.529 13.847 17.019 1.00 11.36 1MBC 96ATOM 10 C LEU 2 -1.183 13.755 18.420 1.00 9.99 1MBC 97ATOM 11 O LEU 2 -1.582 14.772 18.921 1.00 8.99 1MBC 98ATOM 12 CB LEU 2 0.983 14.248 17.119 1.00 10.10 1MBC 99ATOM 13 CG LEU 2 1.692 14.001 15.751 1.00 9.73 1MBC 100ATOM 14 CD1 LEU 2 1.216 14.865 14.716 1.00 8.79 1MBC 101ATOM 15 CD2 LEU 2 3.147 14.217 16.051 1.00 9.54 1MBC 102ATOM 16 N SER 3 -1.114 12.521 18.854 1.00 9.53 1MBC 103ATOM 17 CA SER 3 -1.383 12.274 20.256 1.00 10.47 1MBC 104ATOM 18 C SER 3 -0.208 12.829 21.090 1.00 10.05 1MBC 105ATOM 19 O SER 3 0.833 13.076 20.589 1.00 9.70 1MBC 106ATOM 20 CB SER 3 -1.596 10.794 20.556 1.00 10.87 1MBC 107ATOM 21 OG SER 3 -0.346 10.023 20.222 1.00 11.48 1MBC 108ATOM 22 N GLU 4 -0.513 12.922 22.391 1.00 11.12 1MBC 109ATOM 23 CA GLU 4 0.423 13.415 23.392 1.00 11.78 1MBC 110ATOM 24 C GLU 4 1.495 12.367 23.459 1.00 11.72 1MBC 111

The second column contains a running index over all the atoms, and the third column contains the atom name. In our first exercise we shall be interested in the CA-s only. The alpha carbons (CA) are at the center of the main chain of the protein. All the different amino acids (named at the fourth column) have the same backbone …N-CA-C… and the CA is at the center of it.

Column 5 lists the index of the amino acid.

Columns 6-8 have the x,y,z coordinate of the corresponding atom.

We shall be interested (at least at the beginning) in a reduced representation of protein structures that will include only CA-s.

Note also that some proteins have more than a single chain. A TERminal line indicates the end of a chain

TER 1070 ARG A 141

In this exercise we use only the first chain in a file.

We need a subroutine that will extract from a protein data bank only the CA of the first chain. The functions crd and word that are given below do just that. They are rather complex and at present we shall not discuss them in details. You may use them as is, or dig into MATLAB help file to understand all of their tricks.

Below is a MATLAB routine that performs this function

function crd = pickCA(pdbFileName)

% Read CA protein data from pdb

text file.

fid = fopen(pdbFileName); % Open coordinate file

Eline = fgetl(fid); % Skip till you get to ATOM lines

word = words(Eline); % word-break the line to words separated

by space

% ~ is a logical not. Read next line if

~ TER and ~ ATOM

while (and(~strcmp(word{1},'TER'),~strcmp(word{1},'ATOM')))

Fline

= fgetl(fid); % The

first atom is N

word =

words(Fline);

end

% if TER end of chain

if (strcmp(word{1},'TER')) break; end;

Fline = fgetl(fid); % The second atom is CA

word = words(Fline);

%special protein data bank cases are

handled below

if or(strcmp(word{5},'R')

,strcmp(word{5},'A'))

x=7;

y=8; z=9;

else

x=6; y=7;

z=8;

end

i=0;

while (~strcmp(word{1},'TER'))

i = i+1; % The first atom is CA

coords(i,:) =

[str2double(word{x}),str2double(word{y}),str2double(word{z})];

while (~strcmp(word{1},'TER'))

Fline = fgetl(fid); % Find the CA of the next amino

acid

word =

words(Fline);

if strcmp(word{1},'TER') break; end;

if ~strcmp(word{1},'ATOM') break; end;

if strcmp(word{3},'CA') break; end;

end

if or(strcmp(word{1},'TER'),~strcmp(word{1},'ATOM')) break; end;

end

fclose(fid);

crd = coords(1:i,:);

function word = words(string)

% Break a string into whitespace

delimited words.

% Produces a cell-array of

strings. Individual strings are

% accessed via s{1}, s{2}, and

s{3}. Note the curly braces.

s = size(string,2); % Length of input string

blanks = find(isspace(string)); % Find indices of all whitespace

zblanks = [0 blanks]; % 0 counts as whitespace, too

n = size(zblanks,2); % Number of words (includes length

0)

lengths = [blanks s+1] - zblanks -

1; % Lengths of all words

result = cell(1,n); % Reserve space

for i = 1:n % Copy all words (includes length 0)

result{1,i}

= string(zblanks(i)+1:zblanks(i)+lengths(i));

end

word = result(lengths > 0); % Remove length 0 words

To

read the CA from a protein structure to a MATLAB array do the following:

Connect

to www.rcsb.org and extract a protein

structure of interest.

Read

the file by a call for the above function, in the command window of Matlab.

For

example, to extract HUMAN

GRANULOCYTE MACROPHAGE COLONY STIMULATING FACTOR with a protein-data-bank (pdb) code – 1gmf:

coor = pickCA('Z:\ron\structures\1gmf.pdb');

coor is a two dimensional array (1:n,1:3). The column is the number of the amino acid and the rows are the x,y,z coordinates

To

plot the sequence of CA as a curve in 3D dimension we do:

plot3(coor(:,1),coor(:,2),coor(:,3))

Note

that the “:” picks the complete range of the vector and there is no need to

know or specify the exact dimension.

The

distances between sequential CA in proteins are fixed at approximately 3.8

angstrom, making the connected picture more reasonable.

For

many purposes it is useful to set the geometric center of the protein at the

origin of the coordinate system (for example, applying a rotation matrix to a

system that is not at the origin will have an undesired translational

component). The geometric center is defined

![]()

In

our case the summation is over the coordinates of the CA. A short MATLAB script

that set the geometric center of the molecule to zero is below:

n = size(coor,1);

gc = [sum(coor(:,1)) sum(coor(:,2))

sum(coor(:,3))]/n

for i=1:n

coor(i,:) = coor(i,:)-gc;

end

By

clicking on the right top bottom it is possible to rotate the protein chain in

3D. It is not that easy to understand properties of the structure from the 3D

view. For example, can you identify how many helices are in the structure?

It

is useful to have other, less straightforward representations of the structure

that are nonetheless simpler to analyze.

One interesting representation (in 2D) is the contact matrix. If the distance between a pair of amino

acids ![]() and

and ![]() is less than seven,

the corresponding element in the contact matrix is set to one. Otherwise it is set to zero

is less than seven,

the corresponding element in the contact matrix is set to one. Otherwise it is set to zero

A

short MATLAB script that prepares and draws a contact map is below:

n = size(coor,1);

counter = 0;

for i=1:n

for j=i+1:n

dist = norm(coor(i,:)-coor(j,:));

if (dist<=7)

counter = counter + 1;

x(counter) = i;

y(counter) = j;

end

end

end

plot(x,y,'bd')

We repeat the same exercise for the protein myoglobin (1mbco). Can you suggest a fingerprint for a helix? Beta sheet? Can you identify sharp turns? Explain the off-diagonal elements and what structural features they correspond to.