Alan Shieh <ashieh@cs.cornell.edu>, with sections taken from Harlan, and 2004 Spring Recitation #3

Common mistakes on problem set #1

- Style Issues

- Several people used tuple projections such as: #2 (2.0, "hello"). These should be avoided by using pattern matching when possible.

- People were not breaking their lines at 80 columns. Please do so in the future.

- if-expressions

- It is inappropriate to use an if-statement if the branches just return bare true or false values, for instance

if x then true else false

returns the same value as

x

Instead of writing the if-statement, just write x.

- Similarly, if the if-statement is equivalent to a logical expression, then you should write the logical expression instead. For instance:

if x then if y then true

else false

else false

is simply the same as "x andalso y". In general these sorts of boolean-valued if-expressions can be reduced to a set of boolean operations.

- Pattern matching

- Nested case expressions should be expressed as a single level of case statements. For instance, instead of

case x of

A => ...

| B => ...

| C => (case y of

M => ...

| N => ...)

| D => ...

create a tuple and pattern match on that, as follows:

case (x, y) of

(A, _) => ...

| (B, _) => ...

| (C, M) => ...

| (C, N) => ...

| (D, _) => ...

- If you do choose to use a nested case statement, make sure that you place parenthesis around it! Notice the subtle bug in the following code:

case x of

A => ...

| B => ...

| C => case y of

M => ...

| N => ...

| D => ... (* associated with inner case *)

While the indentation suggests otherwise, the D case is actually associated with the inner case statement on y, and not the outer one on x. With correct indentation, the problem is more obvious.

case x of

A => ...

| B => ...

| C => case y of

M => ...

| N => ...

| D => ...

- Misspelling datatype constructors can cause serious, silent changes to the meaning of your program. Instead of generating the intended pattern match of a particular constructor within a datatype, the pattern will be a variable binding!

For example:

datatype car = PORSHE | PINTO

fun f(x:car):string =

case x of

PORCHE => "hello"

| PINTO => "goodbye!"

Do you notice the subtle bug here? The word PORSHE was spelled incorrectly in the case, so it was assumed to be a variable which we are attempting to bind. That means that the above code is equivalent to:

datatype car = PORSHE | PINTO

fun f(x:car):string =

case x of

y => "hello"

| PINTO => "goodbye!"

In this case SML will see that the PINTO case is redundant since it is unreachable and complain.

- Performance problems

- nth and @ were commonly used to solve Fibonnaci. They are both slow operations that you should avoid where possible. nth walks through the list to fetch an item. @ requires a list walk, and potentially adds a data copy. Hence, these operations are O(n).

nth is ok if you use it to access elements at the beginning of the list, although a pattern match should be more succinct.

- nth and @ were commonly used to solve Fibonnaci. They are both slow operations that you should avoid where possible. nth walks through the list to fetch an item. @ requires a list walk, and potentially adds a data copy. Hence, these operations are O(n).

(* Two Fibonacci implementations.

*

* The first implementation makes gratuitous use of O(n) list

* operations. Hence, the resulting running time will be O(n^2) in

* the length of the output.

*

* The second implementation constructs the output in reverse order.

* Instead of needing to @ (O(n)), we can use :: (O(1)). Instead of

* needing to access elements near the end of the list with nth & length,

* we simply use pattern matching to access the elements at the front

* of the list.

*

* Hence, the helper function runs O(n) in the size of the output.

* Despite the call to rev (O(n)), fiboGood still runs in O(n) total.

*)

fun fiboBad(n:int):int list =

let

fun helper(lst:int list ):int list =

let

(* following length call is O(n), resulting running time O(n^2) *)

val len = length(lst)

in

if(len >= 2)

then

let

val x1 = List.nth(lst, len - 1) (* Same slowness as length *)

val x2 = List.nth(lst, len - 2) (* Same slowness as length *)

val x0 = x1 + x2

in

if x0 <= n then

helper(lst @ [x0])

else lst

end

else

raise Fail "this is never the case"

end

in

case n of

0 => [0]

| _ => if (n<0) then []

else helper([0,1])

end

fun fiboGood(n:int):int list =

let

fun helper(lst:int list ):int list =

case lst of

x1::x2::xs =>

let

val x0 = x1 + x2

in

if x0 <= n then helper(x0::lst)

else lst

end

| _ => raise Fail "this is never the case"

in

case n of

0 => [0]

| _ => if (n<0) then []

else List.rev(helper([1,0]))

end

- Recursively calling fibonacci rather than generating the list in a more iterative fashion is very inefficient, as this results in an exponential number of redundant operations.

Deep pattern matching/constructors

Recitation notes #3 contains some examples of deep pattern matching with lists. Here is another example with syntax trees. A syntax tree is a tree that represents the parsed form of a program in some language -- that is, it is a tree that represents the syntactic, or structural, meaning of a program.

Let us define a polymorphic datatype that we will use to represent the syntax tree of arithmetic expressions consisting of multiply (*), add (+), and literals of some type

datatype 'a AST = Add of 'a AST * 'a AST | Multiply of 'a AST * 'a AST | Value of 'a

Note that each AST node corresponds to either an operation or a value. Each operand of an operation is also an AST node.

Some examples:

(1 + 5) * 2 ==>

Multiply(Add(Value(1), Value(5)), Value(2))

(1 + 5) + (1 + 5) ==>

Add(Add(Value(1), Value(5)), Add(Value(1), Value(5)))

These two expressions are equivalent. From algebra, you know that expressions of the form y * 2 are equivalent to those of the form y + y. We will write a function that converts expressions of the former structure into those of the latter. Expressions that are not of the form y * 2 are not modified. This we accomplish with deep pattern matching:

val t = Multiply(Add(Value(1),Value(5)),Value(2));

fun xform(t:int AST) : int AST =

case t of

Multiply(x,Value(2)) => Add(x,x)

| _ => t;

val t' = xform(t)

Resulting value of t':

Add(Add(Value(1),Value(5)),Add(Value(1),Value(5)))

We use pattern matching to divide possible inputs into two cases. The first case matches any Multiply tree that has 2 as a second operand. The left branch of this tree is replicated twice in constructing the equivalent Add tree. The default case returns the unmodified input.

Tree traversal in SML

Let us define a polymorphic binary tree type:datatype 'a treenode = Tree of 'a * 'a treenode * 'a treenode | Null

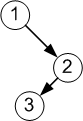

Each tree node is associated with a value and a pair of children. The children are themselves other tree nodes. The value Null is used as a placeholder for a missing child. Example:

Tree(1,Null,Tree(2,Tree(3,Null,Null),Null))

There are three standard tree traversals

- Preorder - Visit the value of the current node, then the children

- Postorder - Visit the children first, then the current node

- Inorder - Visit the left child, then the current node, then the right child

You should be familiar with these tree traversals from previous datastructures & programming classes. Here I will use traversal order to demonstrate polymorphism, pattern matching, and the option datatype (which we will see more of in class).

The recursive structure we use in findPreorder is to first check whether the predicate matches the current value; if so, return. Otherwise, recursively check the children. If the left child contains a match, return that match. Else, the left child does not contain a match, so check the right child.

Let's first define findPreorder in the natural way: as a polymorphic function that takes a 'a tree and 'a predicate, and returns 'a :

(* Find the first element that satisfies pred *)

fun 'a findPreorder (tree : 'a treenode, pred : 'a -> bool) : 'a =

case tree of

Null => ??? (* How do we signal a match failure ? *)

| Tree(self, child0, child1) =>

if(pred self) then

self

else

case findPreorder(child0, pred) of

x => x

(* How do we detect a match failure? *)

| ??? => case findPreorder(child1, pred) of

x => x

| ??? => ???

We run into trouble here at the ??? points. What value should we return from the domain of 'a to signal the lack of a match? We could choose a conventional value, such as -1, or the largest negative number, and add that as an argument:

(* Find the first element that satisfies pred *)

fun 'a findPreorder(tree: 'a treenode, pred: 'a -> bool, nomatch: 'a): 'a =

case tree of

Null => nomatch

| Tree(self, child0, child1) =>

if(pred self) then

self

else

let

val findresult = findPreorder(child0, pred)

in

if(findresult = nomatch)

then

(* process right child *)

...

else

val

end

As you can see, this gets very messy very fast. We can't pattern match against nomatch, so we have to use if expressions. Furthermore, this program won't typecheck: not all types (e.g., real) support the = operator, so the if(val = nomatch) should not be allowed to compile.

Furthermore, nomatch is no longer a valid value in a tree. Consider the following cases

- nomatch occurs, and is the only match. Then findPreorder will return nomatch.

- nomatch occurs, but is not the only match, and is before another match. Then findPreorder will return the second match

- No matches. Then findPreorder will return nomatch.

Case 1 and 3 have indistinguishable results. Case 2 is incorrect behavior: we have not returned the first match.

The SML built-in option polymorphic type provides a convenient solution. option is defined as follows:

datatype 'a option = SOME of 'a | NONE

When you instantiate an option type, you create a type with a new domain: the domain of the original type (say int), and a value (NONE) that cannot/does not occur in the domain of the original type.

(* Find the first element that satisfies pred *)

fun 'a findPreorder (tree : 'a treenode, pred : 'a -> bool) : 'a option =

case tree of

Null => NONE

| Tree(self, child0, child1) =>

if(pred self) then

SOME(self)

else

case findPreorder(child0, pred) of

SOME(x) => SOME(x)

| NONE => case findPreorder(child1, pred) of

SOME(x) => SOME(x)

| NONE => NONE;

To recap, the option solution gives us some nice properties.

- NONE cannot occur in the input tree. The input tree parameterized on 'a; NONE is only valid in 'a option. As a result, the ambiguous cases from before are eliminated

- pattern match directly against the NONE type, rather than write if expressions

Curried Functions

Up to now, we have used tupling to construct functions that take multiple arguments:

fun add (x:int, y:int) : int = x + y

The arguments are expressed as a tuple, and an implicit pattern match is used to bind x and y to the argument values.

Currying is an alternate technique for implementing multiple argument functions. Curried functions allow the programmer to feed in arguments "one at a time". Here is the curried form of the above function

fun add (x:int): int->int =

((fn (y) => x+y) : int->int)

val addOne = (add 1)

==> val it = fn : int -> int

addOne 2

==> val it = 3 : int

add has type int->(int->int). It returns a specialized function that is dependent on the argument. Multiple argument functions are implemented as follows:

(add 1 2)

==> (fn (y) => 1 + y) 2

==> 3

The first argument is passed to the function, evaluating to another function. The second argument is then applied to this function, to yield the final integer result. Applying k arguments to a curried function of k arguments results in k-1 function return values, and k applications.

Here is the sugared (more convenient, succinct, but equivalently powerful) way of defining a curried function in SML:

fun add (x:int) (y:int) = x + y

The "second argument" x here is not an argument to add. The syntax is telling ML that after passing in the argument x, add will return another function which takes in an argument y and returns an int. The distinction here is critical. add takes one argument x and returns a function.

One convenient use of curried functions is in defining predicates. For instance, suppose one has the following equality test

val equality : 'a->'a->bool

We can convert this to a predicate that tests for a value K as follows:

val predicate = equality K ==> 'a->bool

Notes:

- Currying depends heavily on functions as first class values. Currying returns many function values

- The specialization can stop at any step in the evaluation. E.g., one can specialize the first k-1 arguments of a k argument curried function.

- It is possible to write SML that converts from curried functions to standard (tupled) and vice versa

- The type signatures in currying highlight the significance of parenthesization in types. int->(int->int) (which is equivalent to int->int->int, due to the default associativity of ->), is quite different from (int->int)->int. The former takes an int and returns a function, while the latter takes a function from int to int, and returns an int.

Higher order functions: ''map'', ''fold{r,l}''

map

Last week we introduced the map higher order function. 'map works as follows: map(fn,list) ==> apply fn to every element in list, e.g.

map f [l0,l1,l2] ==> [f(l0),f(l1),f(l2)]

This week, we'll generalize map as much as we can with polymorphism. Let us just consider the signature; the body of the function will not change.

A first signature might be

fun 'a map (f:'a->'a, l:'a list) : 'a list

This allows us to take any list type as an argument. However, we are restricted to returning the same list type. Suppose we want to remove this restriction:

fun ('a, 'b) map (f:??, l:'a list) : 'b list

What signature do we need to use for f? Well, recall that f takes elements from the input list to the output list. So f must have signature 'a->'b .

fun ('a, 'b) map (f:'a->'b, l:'a list) : 'b list

As mentioned in lecture, the built-in map is actually in the curried form. One can rewrite uncurried map to the curried map.

fold{l,r}

Recall how foldl works:

(* acc is the "accumulator" *)

foldl(f,acc,[l_0,l_1,l_2]) ==>

f(l_0,f(l_1,f(l_2,acc)))

A couple of observations:

- f has return type of acc

- foldl has return type of acc (same as f)

- The second argument of f has the same type as the return type of f', and the type of acc

- The first argument of f has the same type as the type of the list elements

Let's generalize foldl as we did with map. Again, last week we had a rather specialized, uncurried form:

foldl : ((int * int)->int * int * int list)->int

Here is an incremental example of building the appropriate type signature. Let's parameterize the return value and the list elements

('a, 'b) foldl : ((?? * ??)->?? * ?? * 'a list)->'b

We need to fill in all the ??'s. From constraint

2:

('a, 'b) foldl : ((?? * ??)->?? * 'b * 'a list)->'b

1:

('a, 'b) foldl : ((?? * ??)->'b * 'b * 'a list)->'b

3:

('a, 'b) foldl : ((?? * 'b)->'b * 'b * 'a list)->'b

4:

('a, 'b) foldl : (('a * 'b)->'b * 'b * 'a list)->'b

Let's step back and analyze what we've done. We started with a description of how foldl should operate on its arguments, and constrained the types of its last argument and the return value. Then, based on our informal definition of foldl, we propagated the constraints to the rest of the signature.

We've in effect done the inverse of the type checking operation in SML: given a desired result, we specify the type variables so as to pass type checking. Note, however, that SML does this checking on the function itself, not the informal definition. We could have done so as well, but that probably would have been harder. Doing these steps at a different level of abstraction gives us an opportunity to sanity check our assumptions on two different "implementations."

More uses of fold

We'll now turn to applications of fold.

For convenience, we will use the curried version of fold

- sum - add up a list of numbers

val sum : int list -> int = foldl (op +) 0

- multiply - multiply a list of numbers

val multiply : int list -> int = foldl (op * ) 1

- concat - concatenate a list of strings

val concat : string list -> string = foldr (op ^) ""

- filter - return the list of elements that satisfy predicate

fun 'a filter (pred:'a->bool) : 'a list -> 'a list =

foldr

(fn (x:'a, y:'a list) =>

if(pred(x)) then

x::y

else

y)

[]

- partition - Return (list0, list1). Given a predicate, place the elements that satisfy the predicate in list0, and the ones that don't in list1

fun 'a partition (pred:'a->bool) : 'a list -> ('a list * 'a list) =

foldr

(fn (x:'a, (l0:'a list, l1:'a list)) =>

if(pred(x)) then

(x::l0, l1)

else

(l0, x::l1))

([],[])

If you are still confused about fold, here are two different analogies for its mode of operation.

- Analogy with imperative languages: the accumulator as information that passes between the list elements. In C or Java, this would be a variable that is not destroyed between loop iterations, and is updated on each iteration. For instance:

int sum;

for(i=0; ... ; i++) {

sum += list[i];

}

Here, sum is an accumulator.

- Here's a real-world analogy. Suppose I want to collect homework from students during section. I will walk to each student. As I to each student, I add that student's homework to the pile in my hand. In this case, the "pile" is the accumulator, and the "list elements" is the students. My "function" is to extract the homework from each student, and add it to my pile (accumulator). Note that I start with an empty pile, and end with a big pile.