Variants

Today we'll practice with variants and other user-defined data types, learn more about pattern matching, define binary tree data structures with variants, and learn about two more OCaml features, exceptions and polymorphic variants.

Data types

Exercise: cards [✭✭]

Define a variant type

suitthat represents the four suits, ♣ ♦ ♥ ♠, in a standard 52-card deck. All the constructors of your type should be constant.Define a type

rankthat represents the possible ranks of a card: 2, 3, ..., 10, Jack, Queen, King, or Ace. There are many possible solutions; you are free to choose whatever works for you. One is to makerankbe a synonym ofint, and to assume that Jack=11, Queen=12, King=13, and Ace=1 or 14. Another is to use variants.Define a type

cardthat represents the suit and rank of a single card. Make it a record with two fields.Define a few values of type

card: the Ace of Clubs, the Queen of Hearts, the Two of Diamonds, the Seven of Spades.

□

Pattern matching

Exercise: matching [✭]

For each pattern in the list below, give a value of type

int option list that does not match the pattern and is

not the empty list, or explain why that's impossible.

(Some x)::tl[Some 3110; None][Some x; _]h1::h2::tlh :: tl

□

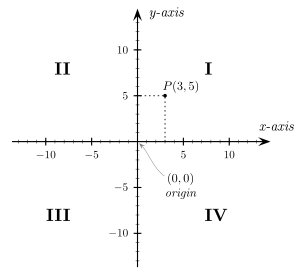

Exercise: quadrant [✭✭]

Complete the quadrant function below, which should return the quadrant

of the given x, y point according to the diagram on the right (borrowed from Wikipedia).

Points that lie on an axis do not belong to any quandrant. Hints: (a) define a helper function

for the sign of an integer, (b) match against a pair.

type quad = I | II | III | IV

type sign = Neg | Zero | Pos

let sign (x:int) : sign =

...

let quadrant : int*int -> quad option = fun (x,y) ->

match ... with

| ... -> Some I

| ... -> Some II

| ... -> Some III

| ... -> Some IV

| ... -> None□

There is an extended syntax for pattern matching:

match e with

| p1 when g1 -> e1

| ...

| pn when gn -> enThe gi here are Boolean expressions much like the guard of an if expression.

Each of the when gi clauses is optional. If they occur, then branch i

is chosen only if pi matches e and gi evaluates to true.

Exercise: quadrant when [✭✭]

Rewrite the quadrant function to use the when syntax. You won't need

your helper function from before.

let quadrant_when : int*int -> quad option = function

| ... when ... -> Some I

| ... when ... -> Some II

| ... when ... -> Some III

| ... when ... -> Some IV

| ... -> NoneBinary trees

Here is a definition for a binary tree data type:

type 'a tree =

| Leaf

| Node of 'a * 'a tree * 'a treeA node carries a data item of type 'a and has a left and right subtree. A leaf

is empty. Compare this definition to the definition of a list and notice how

similar their structure is:

type 'a tree = type 'a mylist =

| Leaf | Nil

| Node of 'a * 'a tree * 'a tree | Cons of 'a * 'a mylistThe only essential difference is that Cons carries one sublist, whereas

Node carries two subtrees.

Here is code that constructs a small tree:

(* the code below constructs this tree:

4

/ \

2 5

/ \ / \

1 3 6 7

*)

let t =

Node(4,

Node(2,

Node(1,Leaf,Leaf),

Node(3,Leaf,Leaf)

),

Node(5,

Node(6,Leaf,Leaf),

Node(7,Leaf,Leaf)

)

)The size of a tree is the number of nodes in it (that is, Nodes, not Leafs).

For example, the size of tree t above is 7. Here is a function

function size : 'a tree -> int that returns the number of nodes in

a tree:

let rec size = function

| Leaf -> 0

| Node (_,l,r) -> 1 + size l + size rExercise: depth [✭✭]

Write a function depth : 'a tree -> int that returns the number of

nodes in any longest path from the root to a leaf. For example, the

depth of an empty tree (simply Leaf) is 0, and the depth of tree t

above is 3. Hint: there is a library function max : 'a -> 'a -> 'a

that returns the maximum of any two values of the same type.

□

Exercise: shape [✭✭✭]

Write a function same_shape : 'a tree -> 'b tree -> bool that determines whether

two trees have the same shape, regardless of whether the values they carry at each node

are the same. Hint: use a pattern match with three branches, where the expression

being matched is a pair of trees.

□

Exceptions

OCaml has an exception mechanism similar to many other programming languages. Exceptions are essentially variants. A new type of OCaml exception is defined with this syntax:

exception E of twhere E is a constructor name and t is a type. The of t is optional.

Notice how this is similar to defining a constructor of a variant type.

To create an exception value, use the same syntax you would for creating

a variant value. Here, for example, is an exception value whose constructor

is Failure, which carries a string:

Failure "something went wrong"This constructor is pre-defined in the standard library (scroll down to "predefined exceptions") and is one of the more common exceptions that OCaml programmers use.

To raise an exception value e, simply write

raise eThere is a convenient function failwith : string -> 'a in the standard library

that raises Failure. That is, failwith s is equivalent to raise (Failure s).

(Often we use this function in the assignment release code we ship to you.)

Exercise: list max exn [✭✭]

Write a function list_max : int list -> int

that returns the maximum integer in a list, or raises

Failure "list_max" if the list is empty.

□

To catch an exception, use this syntax:

try e with

| p1 -> e1

| ...

| pn -> enThe expression e is what might raise an exception. If it does not, the entire

try expression evaluates to whatever e does. If e does raise an exception value

v, that value v is that matched against the provide patterns, exactly like

match expression.

Exercise: list max exn string [✭✭]

Write a function list_max_string : int list -> string

that returns a string containing the maximum integer in a list, or

the string "empty" (note, not the exception Failure "empty" but

just the string "empty") if the list is empty. Hint: string_of_int in

the standard library will do what its name suggests.

□

If it is part of a function's specification that it raises an exception, you might want to write OUnit tests that check whether the function correctly does so. Here's how to do that:

open OUnit2

let tests = "suite" >:::

[

"empty" >:: (fun _ -> assert_raises (Failure "hd") (fun () -> List.hd []));

"nonempty" >:: (fun _ -> assert_equal 1 (List.hd [1]));

]

let _ = run_test_tt_main testsThe expression assert_raises exc (fun () -> e) checks to see whether expression e

raises exception exc. If so, the OUnit test case succeeds, otherwise it fails.

Note: a common error is to forget the (fun () -> ...) around e. If you do,

the OUnit test case will fail, and you will likely be confused as to why. The reason

is that, without the extra anonymous function, the exception is raised before

assert_raises ever gets a chance to handle it.

Exercise: list max exn ounit [✭]

Write two OUnit tests to determine whether your solution to list max exn, above, correctly raises an exception when its input is the empty list, and whether it correctly returns the max value of the input list when that list is nonempty.

□

Dictionaries

Recall from the previous lab that an association list is a list of pairs that implements a dictionary, and that insertion in an association list is constant time, but lookup is linear time.

A more efficient dictionary implementation can be achieved with binary search trees. Each node of the tree will be a pair of a key and value, just like in an association list. Furthermore, the tree obeys the binary search tree invariant: for any node n, all of the values in the left subtree of n have keys that are less than n's key, and all of the values in the right subtree of n have keys that are greater than n's key. (We do not allow duplicate keys.)

For example, here is a binary search tree representing the same dictionary as that in exercise assoc list in the previous lab:

let d =

Node((2,"two"),

Node((1,"one"),Leaf,Leaf),

Node((3,"three"),Leaf,Leaf)

)The following exercises explore how to implement a binary search tree.

Exercise: lookup [✭✭]

Write a function lookup : 'a -> ('a*'b) tree -> 'b option

that returns the value associated with the given key, if it is present.

□

Exercise: insert [✭✭✭]

Write a function insert : 'a -> 'b -> ('a*'b) tree -> ('a*'b) tree

that adds a new key-value mapping to the given binary search tree. If the key

is already mapped in the tree, the output tree should map the key to the

new value.

□

Exercise: is_bst [✭✭✭✭]

Write a function is_bst : ('a*'b) tree -> bool that returns true if

and only if the given tree satisfies the binary search tree invariant.

An efficient version of this function that visits each node at most once

is somewhat tricky to write.

Hint: write a recursive helper function that takes a tree and either

gives you (i) the minimum and maximum value in the tree, or (ii) tells

you that the tree is empty, or (iii) tells you that the tree does not

satisfy the invariant. Your is_bst function will not be recursive, but

will call your helper function and pattern match on the result. You

will need to define a new variant type for the return type of your helper

function.

□

A truly efficient binary search tree should be balanced: the depths of various paths through the tree should all be about the same. One famous balanced tree data structure is the 2-3 tree, invented by Cornell's own Prof. John Hopcroft in 1970.

Polymorphic variants

Thus far, whenever you've wanted to define a variant type, you have had to give

it a name, such as day, shape, or 'a mylist:

type day = Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat

type shape =

| Point of point

| Circle of point * float

| Rect of point * point

type 'a mylist = Nil | Cons of 'a * 'a mylistOccasionally, you might need a variant type only for the return value of a single

function. For example, here's a function f that can either return

an int or ∞; you are forced to define a variant type to represent

that result:

type fin_or_inf = Finite of int | Infinity

let f = function

| 0 -> Infinity

| 1 -> Finite 1

| n -> Finite (-n)The downside of this definition is that you were forced to defined

fin_or_inf even though it won't be used throughout much of your program.

There's another kind of variant in OCaml that supports this kind of programming: polymorphic variants. Polymorphic variants are just like variants, except:

- You don't have declare their type or constructors before using them.

- There is no name for a polymorphic variant type. (So another name for this feature could have been "anonymous variants".)

- The constructors of a polymorphic variant

start with

`(this the "grave accent", also called backquote, back tick, and reverse single quote; it is typically found on the same key as the~character, near the escape key).

Using polymorphic variants, we can rewrite f:

(* note: no type definition *)

let f = function

| 0 -> `Infinity

| 1 -> `Finite 1

| n -> `Finite (-n)With this definition, the type of f is

val f : int -> [> `Finite of int | `Infinity ]This type says that f either returns `Finite n for some n:int

or `Infinity. The square brackets do not denote a list, but rather

a set of possible constructors. The > sign means that any code that

pattern matches against a value of that type must at least handle the

constructors `Finite and `Infinity, and possibly more. For

example, we could write:

match f 3 with

| `NegInfinity -> "negative infinity"

| `Finite n -> "finite"

| `Infinity -> "infinite"It's perfectly fine for the pattern match to include constructors other

than `Finite or `Infinity, because f is guaranteed never to

return any constructors other than those.

Exercise: quadrant poly [✭✭]

Modify your definition of quadrant to use polymorphic variants. The types of your functions should become these:

val sign : int -> [> `Neg | `Pos | `Zero ]

val quadrant : int * int -> [> `I | `II | `III | `IV ] option□

There are other, more compelling uses for polymorphic variants that we'll see later in the course. They are particularly useful in libraries. For now, we generally will steer you away from extensive use of polymorphic variants, because their types can become difficult to manage.