**CS 1109: Fundamental Programming Concepts (Summer 2023)**

[Home](../index.md.html) • [Schedule](../schedule.md.html) • [Syllabus](../syllabus.md.html) • [Assignments](../assignments.md.html) • [Labs](../labs.md.html)

(#) Lab 1: Getting Started with Python

In this lab, we will set-up Python and Virtual Studio Code on your personal computers. Afterwards, you will write your first Python program and experiment with evaluating expressions in the Python interpreter.

!!! note: Due Date

This lab is due **Monday, June 26th, 2023 at 11:30am EDT**.

(#) Installing Python

As you very well know by this point, we will be using [Python](https://python.org)[^python] as the programming language for this course. There are many different ways to install Python, but perhaps the easiest is installing the Anaconda Python distribution.

To do so, navigate your web browser to [](https://www.anaconda.com/download/). Click on the "Download" button and install using the standard installation process for your operating system. If you get stuck, let me know.

We will check that the installation was successful after we install the text editor for the course: Visual Studio Code.

(#) The Visual Studio Code programming environment

(##) Introduction

As we have discussed in class, the design of algorithms are central to computer science. While simply designing algorithms to solve problems is an entire area of research on its own, most of the time we would like to express those algorithms in a form that can be understood and processed by computers (i.e., programming languages). This is ultimately what we call *programming*.

One of the most basic tools in a programmer's toolbox is a *text editor*. A text editor is a program that enables you to create and edit *plain text* files. By plain text, we simply mean data which is wholey comprised of characters without any graphical representation attached to it. For example, you likely have come across a `.txt` file, which is one type of plain text file. This is in contrast to *rich text* documents, which combine readable material alongside the presentation of said material, such as **bolded** or *italicized* text, fonts, and colors. The *de facto* example for a rich text file is a Microsoft Word `.doc` file [^word].

Nowadays, however, most programmers write code in a *program-development environment* or *integrated development environment* (IDE) as opposed to a text editors. IDEs go well beyond the capabilities of simple text editors by providing built-in ways to test and debug programs, formatting them for readability, and execute them, among many, *many* other features.

For this course, we will be using *Visual Studio Code* IDE (often abbreviated as "VSCode" or even just "Code"). VSCode is a free, highly configurable, industrial-strength editor developed by Microsoft. You can use VSCode to program in any language and is actively used in professional settings. While you may choose to use an alternative editor, I *highly* suggest using VSCode as it works on any operating system, is actively developed, is relatively easy to pickup, and is one of the most advanced editors at the present. It will prove to be a useful addition to your computer science toolbox!

(##) Installing VSCode

Download Visual Studio Code here: [](https://code.visualstudio.com). Follow the standard installation process for your operating system to install VSCode. If you get stuck, let me know.

(##) Configuring VSCode for CS 1109

Recent versions of VSCode include a profile feature which enable quick changes to settings. This is how we will configure VSCode for this class. Download the profile for this class and save it somewhere you will remember.

Click here to download the `cs1109.code-profile`.

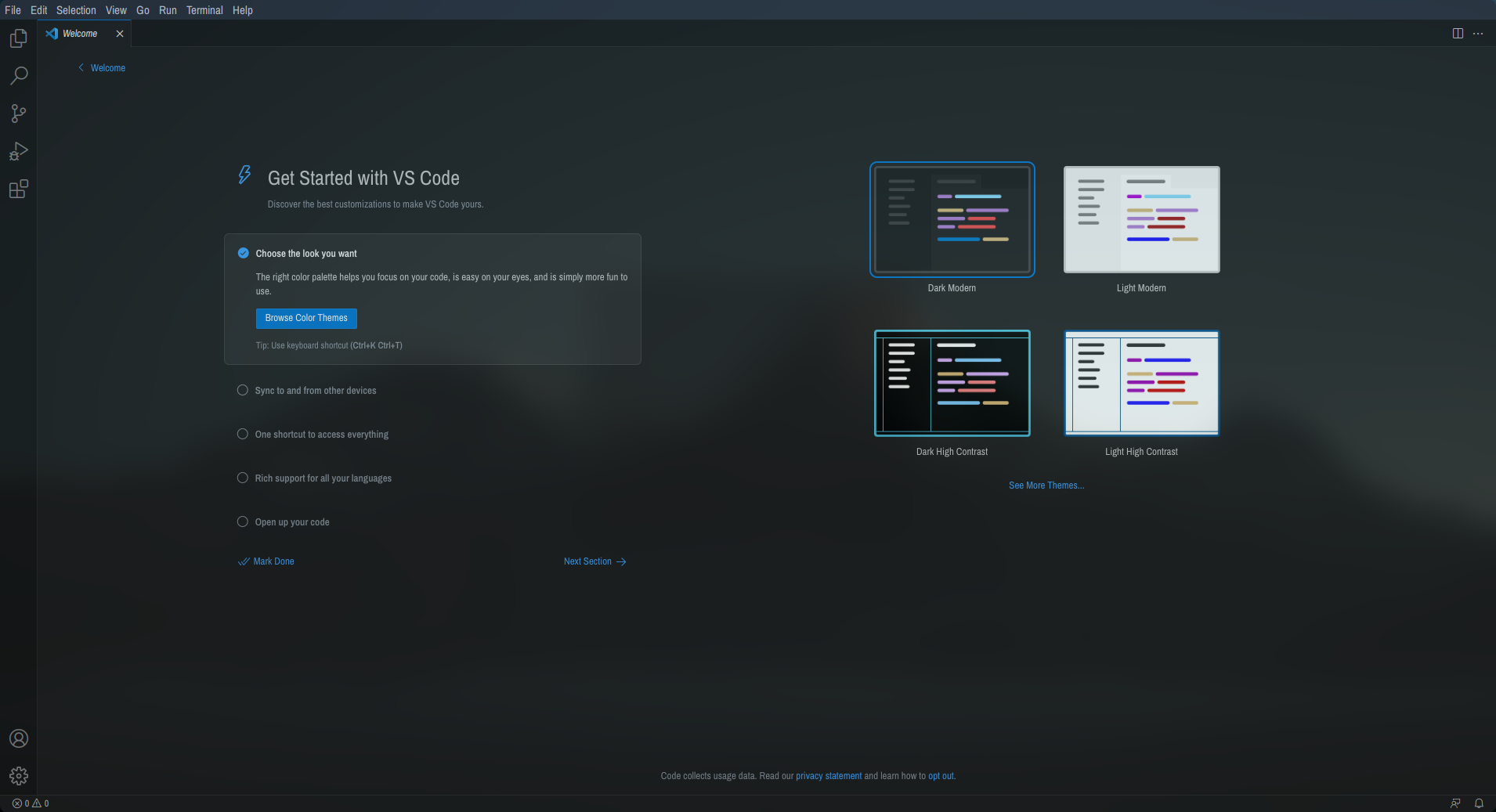

Now open VSCode. When you first open the editor you should see a screen similar to this:

The first thing we are going to do is set-up VSCode for using Python in this class.

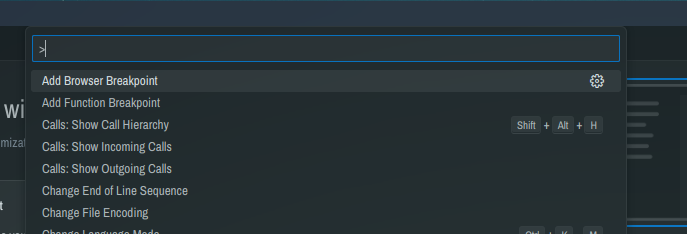

One of the more powerful features of VSCode is the *command palette*. The command palette allows you to execute commands which can modify VSCode settings, run a program, and much more. To open the command palette, use the keyboard shortcut **Cmd + Shift + P** on macOS (**Ctrl + Shift + P** on Windows) or navigate to **View --> Command Palette...**.

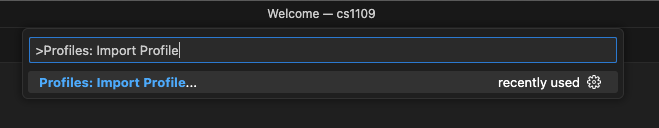

Now type "Profiles: Import Profile" into the command palette.

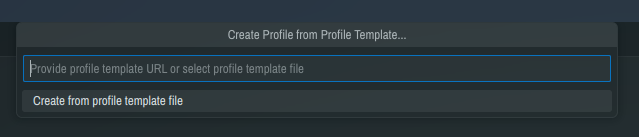

The command palette should now be asking you where the profile you'd like to import is:

Press `Enter` to open up a file selection window. Navigate to where you downloaded a copy of [cs1109.code-profile](../assets/cs1109.code-profile download) and select it. All the settings and extensions required for this course will be set-up. Please feel free to modify any appearance settings (such as your font and theme settings) after class.

!!! ERROR

Please do **not** re-enable any autocomplete functionality, particularly IntelliSense.

These features are quite handy but they can get in the way when you're beginning to learn a language (especially your first one!). You will likely be overwhelmed by the number of autocompletions presented to you, including results from libraries which you are generally not allowed to use in the programming assignments for this course.

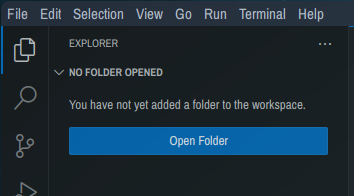

In the top left-hand corner of your screen, click on the top icon in the left-hand sidebar. This will open the *explorer sidebar* where you will be able to manage your files.

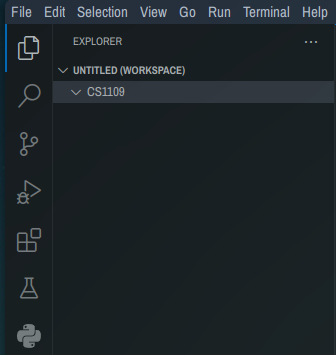

Next, somewhere on your computer create a folder where you will store all the code you will write for this course, such as `cs1109`. Once created go back into VSCode, click on the blue "Open Folder" button, and select the folder that you just made. The explorer sidebar should update and show the (empty) contents of the folder.

(##) Python & VSCode

Now we will tell VSCode about your Python installation, and in the process, verify that everything is working correctly!

Open up the command palette again by using the shortcut **Cmd + Shift + P** on macOS (**Ctrl + Shift + P** on Windows).

Type "Python: Select Interpreter" into the command palette and press `Enter`. Press `Enter` again to confirm that you want to set the interpreter for the folder you created in the last section. Hopefully now you will see the version of Python that you installed at the beginning of this lab. Use the arrow keys or the mouse to confirm the interpreter for Python.

!!! WARNING

If you do not see any Python interpreters to select, please call me over and I will help you fix the error.

**Do not pass this point in the lab until you have selected a Python interpreter.**

(#) Exercise 1: "Hello, World!"

In this exercise, you will write your first Python program. It is tradition to write the "Hello, World!" program which simply displays the greeting "Hello, World!".

1. In VSCode, create a new file by navigating to the explorer sidebar on the left-hand side of your screen and clicking on the icon that looks like a piece of paper with a "+" in the bottom right-hand corner (it should be the leftmost button on the same line as "Untitled (Workspace)").

2. Name the newly created file by typing `hello.py` into the textbox that appears. Note that the file ends in a `.py` file extension signifying that the file contains Python source code.

!!! WARNING

VSCode identifies Python programs using the `.py` file extension. Without the `.py` VSCode will not know what programming language the file is written in.

3. Type the following text into your freshly made `hello.py` file. **Please actually type the text rather than copy-and-pasting in order to get a feel for how VSCode operates while programming.**

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Python listing

# hello.py

# YOUR NAME

# 2023-06-23

#

# "Hello, World!", Python edition

print("Hello, World!")

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

!!! note: Comments in Python

Comments are text that appears in code but is ignored by the computer. In Python, any text after a `#` is a comment.

Examples:

* `# I am a comment`

* `print("Hello, World!") # I am also a comment`

4. Save `hello.py`.

5. Execute your program either by clicking the "Run" button which appears as a ▶ button in the top right-hand portion of your screen. Alternatively, you can execute the program by typing "Python: Run Python File in Terminal" in the command palette or by pressing the **F5** key on your keyboard.

!!!

Recall that you can open the command palette using the keyboard shortcut **Ctrl + Shift + P**.

6. The *Terminal pane* should appear at the bottom of VSCode with the terminal command that was executed along with the output of your program.

Congratulations on writing your first Python program! You are now officially a Python programmer!

(#) Exercise 2: The Python REPL

In Exercise 1, you wrote a Python program and then executed the program by passing the file to the Python interpreter. There is another useful mode that you can use to interact with the Python interpreter: The Python REPL.

REPL stands for **Read, Evaluate, Print, Loop** and it allows the user to enter a line of Python code into the REPL and the interpreter will *read* the line, *evaluate* the code, *print* the result of evaluating the code, and *loop* back to the beginning of the process (i.e., back to read!).

1. Open the Python REPL in VSCode by opening the command palette and enter the command "Python: Start REPL". This will open up a new terminal pane which should look similar to the following:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ python listing

Python 3.11.3 (main, Jun 5 2023, 09:32:32) [GCC 13.1.1 20230429] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

2. Type the following line into the REPL and see what happens.

~~~ Python listing

>>> print("Hi, REPL!")

~~~

!!! WARNING

Do not actually type the `>>>` into the REPL. I have included them in the above code to signify that I am typing this into the REPL.

3. Close the REPL either by pressing `DEL` on your keyboard (this will close the entire REPL window pane in VSCode) or type the following

~~~ Python listing

>>> exit()

~~~

(#) Exercise 3: Arithmetic Operations

One of the most basic building-blocks of most programs are arithmetic expressions. Python provides a number of *operators* that represent common computations such as addition or multiplication.

1. Open the REPL again as you did in Exercise 2. You may have to close the REPL window by right-clicking on the REPL terminal on the rightmost-pane and selecting "Kill Terminal" before re-executing the "Python: Start REPL" command.

2. Try evaluating some of the following arithmetic expressions in the REPL. Before executing each expression, try to predict what Python will print out.

Please feel free to experiment and try expressions and symbols that don't appear in the list below! Try and make some mistakes to see what happens.

* `2 + 3`

* `3 * 9`

* `5 + -1`

* `"2" + "3"`

* `4 ** 2`

* `3 / 2`

* `3 // 2`

* `3 % 2`

* `2 + 3.0`

3. Try and figure out what the `//` and `**` operators do. Experiment with different expressions to try and deduce what mathematical operator they are implementing. Feel free to talk to a fellow classmate and once you are confident in your answer, call me over to verify!

4. Try executing a few of these more complicated expressions. As before, try and compute the result on paper before having Python evaluate the expression for you!

* `3 + 2 * 5`

* `-1 * (2 + 6)`

* `- (2 + 6)`

* `2 ** 3 * 4 // 6`

* `3 - 4 % 2`

What can you conclude about how arithmetic expressions involving more than one operator are evaluated in Python?

5. Combining division and remainder with negative numbers can yield some perplexing results. Same as before, try and predict the result before evaluating the expression. What Python outputs may surprise you. Can you find any patterns?

* `-3 / 2`

* `3 / -2`

* `-3 % 2`

* `2 % -3`

(#) Exercise 4: Mistakes will be made

The REPL is a great way to experiment in Python (or any language that has one!). Making mistakes is not only part of life, but is a **reality** in programming. If you're unsure how something works, just try it out! Nothing bad can happen in the REPL (hopefully!) and it is better to make mistakes on purpose now instead of when you're working on real-world software!

For this exercise, try and predict what Python will do to handle each possible mistake. If you get an error message, try and decipher what it is trying to tell you.

1. In a `print` statement, what happens if you leave out one of the parentheses, or both?

2. If you are trying to print a string, what happens if you leave out the quotation marks? What if you replace the quotation marks with single quotes (i.e., `'hello'` instead of `"hello"`)?

3. Some of the arithmetic expressions in exercise 3 contained negative numbers (e.g., `-3`). We place a single hyphen in front of a numerical value to make it negative. What happens if you instead put a `+` in front of a number? What would `2++3` evaluate to? What if you put multiple hyphens in front of a number (e.g., `--3`)

4. In math, you can prepend leading zeroes to a number and doing so does not change its underlying vlaue. For example, 09 is really the same number as 9. Is this the case in Python?

(#) Exercise 5: Types, types, and more types!

A **type** is a set of values along with operations over these values. This is so important I'm going to put this definition in its own special box:

!!! tip: **Type**

A set of values along with operations over these values.

For example, `int` is a type in Python. Some values of type `int` are `3`, `51`, and `-7`. Some operations for `int`s are `+`, `-`, and `*`.

1. The `type` function will return the type of a value or variable.

~~~ Python listing

>>> type(3)

<class 'int'>

~~~

The word "class"[^class] is used in the sense of a *category*; a type is a *category* of values with associated operations.

Try using the `type` function on other values. What happens if you try and call `type` on the `print` function (i.e., `type(print)`?

2. Is there a maximum value for `int`s? Try evaluating the following expressions in the REPL.

* `2 ** 100`

* `2 ** 1000`

* `2 ** 10000`

3. The `float` type represents real numbers (e.g., 1.5, -9.2103, and $\pi$). A `float` is specified by the inclusion of a decimal point, such as `3.2`.

For each of the following expressions, predict what the output is before evaluating in the REPL.

* `type(2)`

* `type(2.0)`

* `3 * 2.5`

* What is the type of this expression?

* Why is it that type?

* `13.92e6`

4. Is there a maximum value for `float`s? Try evaluating the following expressions in the REPL and compare the results to the results you got for `int`s.

* `2.0 ** 100`

* `2.0 ** 1000`

* `2.0 ** 10000`

5. Predict what the following expression evaluates to.

~~~ Python listing

>>> 0.1 + 0.2

?

~~~

Why might this be happening? Call me over once you have a guess, or if you have no idea!

6. The last type we will cover here is `str`, or the string type. A `str` represents text, such as `"hello"`, `"Zach"`, and `"CS 1109"`.

One operation over `str`s is the `+` operator which performs *string concatenation*. For example:

~~~ Python listing

>>> "CS" + "1109"

"CS1109"

~~~

You might be asking yourself, "But wait, I thought `+` was for addition?" Well, you are correct! In programming languages, this phenomenon is generally called *operator overloading*. In Python, the meaning or the *semantics* of the `+` operator changes depending on the types of the values you give to the `+` operator.

For example, `+` means addition in the expression `2 + 3` as `2` and `3` are both of type `int` whereas `+` refers to concatenation in the expression `"abc" + "def"` as `"abc"` and `"def"` are both of type `str`.

For each expression, try and predict what the result is before evaluating in the REPL.

*