The Macintosh at Dartmouth

The dilemma

In the early 1980s, Dartmouth faced a dilemma in deciding how to use personal computers. The success of the timesharing system could have been a barrier to change. It was much more user-friendly than the primitive environments provided by the Apple II or IBM PC, it was much faster for scientific computation, and it was cheaper per user than personal computers. The Kiewit Network already provided a campus email service and access to the library catalog. Yet when we looked at the trends we saw such rapid improvements in personal computers that they were clearly the path of the future. The Apple II already had a large pool of educational applications and the IBM PC had applications such as word processing and spreadsheets that were far superior to anything that we could produce locally.

Dartmouth had a number of advantages. Dartmouth is large enough to have substantial resources but small enough to be more nimble than larger universities. We had a strong technical staff with close relationships to the faculty. The emphasis on timesharing had made us experts in campus networking. Most importantly, Dartmouth was accustomed to being a leader in academic computing and wanted to remain so.

The solution to this dilemma was to envisage a dual role for a personal computer. A small computer could be used by itself for the tasks that it did well, such as spreadsheets and word processing, but it would also be a terminal to the time sharing system, library catalog, and other network services. Recollections are notoriously unreliable, and I have no records of the process by which this concept emerged, but I remember two key events.

We were all concerned that people at Dartmouth would reject personal computers because of their crude user interfaces, but in late 1982, I heard a leak about a secret Apple project called the Macintosh, and learned extensive technical information about it. When our first Apple sales representative visited us she was horrified to hear of the leak, but after I suggested that we might buy a thousand she arranged for me to visit the Macintosh group in California. I came home convinced that the Macintosh had the potential to succeed at Dartmouth and that Apple was a good company to do business with.

The next event was in spring 1983. The provost, Agnar Pytte, attended a meeting of provosts from other universities where computing strategies were discussed. I provided him with a set of planning slides. One morning soon afterwards he called me to say that he was meeting with the president that afternoon and planned to propose universal ownership of personal computers for Dartmouth freshmen. I hastily put together a short briefing paper. I do not have a copy of that paper, but the main points were to use a personal computer as a terminal to the timeshared computers and the library catalog, to extend the network into every dormitory room, and to use our existing organization to support the initiative. I included an outline budget, which he wisely did not show to the president, but otherwise this paper became the basis for our personal computing plan. Pytte's idea was to begin with the class that entered in fall 1985, but because of a miscommunication when we talked over the telephone I gave him a plan for 1984. He noticed the mistake just before his meeting, gave me a quick call, and kept the 1984 date when he presented the plan to the president.

This paper did not specify which type of computer we would select. I was personally enthusiastic about the Macintosh and lukewarm about the alternatives, but the president came from a commercial background and his ideas about computing were fixated on IBM. IBM wanted us to adopt a stripped out computer known as the PC Junior and Digital made a strong effort to persuade us to adopt their Rainbow computer. The Macintosh project was top secret and I was the only person at Dartmouth who had seen one, but eventually Apple was persuaded to demonstrate the prototype to a group of a dozen people. At the end of the demonstration, Pytte said, "I think that the humanities faculty would like that," and the decision was made. It was typical of Dartmouth that the user interface was the decisive factor in the decision.

The early Macintosh

An early Macintosh

This picture shows the distinctive shape of the first Macintoshes. It had 128Kbytes of memory and a single 3½" diskette with a capacity of 400Kbytes. The small size helped when using the computers in dormitory rooms.

© 1984 Stuart Bratesman - All rights reserved

It is hard to recall just how primitive the Macintosh was when it was released in winter 1984. It was slow, with very limited memory, and had only a single diskette, so that copying files was nearly impossible. There were only two applications: MacWrite, a word processor that crashed when it ran out of memory, and a pixel editor called MacPaint. A decent spreadsheet, Microsoft Multiplan, followed soon afterwards, but the terminal emulator, MacTerminal, was not released until late summer.

Yet the Macintosh had some features that appealed enormously to a segment of the academic community. First, it appealed to the eye. The machine itself was cute, the screen display was attractive, and accessories such as the traveling case were well designed and well made. For the first time we had a computer that was intuitive to use. When he first showed me the machine, Dan'l Lewin of Apple dumped the prototype on the table in its traveling case and went to fetch coffee. By the time that he returned I had set up the machine and was moving windows about on the desktop. I still have the coffee mug.

From the day that it was launched, the Macintosh was a joy to use. It was a complete transformation from the command line interfaces used by other computers. Microsoft took ten years to produce a similar interface with Windows 95. Text is central to academic life and the Macintosh was the first moderately priced computer to support full characters sets, including diacritics, and to use bitmapped fonts for both the screen and the printer.

Without acceptance by a few universities the Macintosh might well have died as so many other personal computers did during that period. When commercial companies saw the early Macintosh they saw a toy with very little software that was a brute to program. Their price was more than twice the deeply discounted price that we paid. Companies looked at the Macintosh and did what they had always done: they bought from IBM. As the saying went, "Nobody ever lost their job by buying from IBM."

Dan'l Lewin, the head of university marketing, was the person who saved the Macintosh. When I first met him he showed me the draft of an agreement for what became the Apple University Consortium. The basic idea was to offer Macintoshes to selected universities for a very low price, $1,000. At that time, we were wrestling with contracts from IBM's lawyers who wanted to use mainframe concepts for the sale of personal computers. It was a joy to read Lewin's straightforward draft and be invited to suggest changes that would make it more acceptable to universities. Unlike IBM, Apple made no attempt to state what our community would do with the machines or to guarantee how many we would sell, both of which are impossible commitments for universities.

About a dozen leading universities joined the Apple University Consortium before the formal release of the Macintosh and Apple supported us well over the years. Dartmouth was unusual in that most of the other universities offered Macintoshes as one of several brands of computer that they supported, but we were determined to select one brand and to put all our effort into it. Drexel was the first university to select the Macintosh for all its students, but Apple particularly valued Dartmouth's reputation in educational computing. While IBM and Digital were prepared to make major gifts to gain our business, Apple was more restrained except for the deep discounting, However, they gave us a grant of several machines, which we used as seed machines for faculty to use in education.

The Macintosh at Dartmouth

When Dartmouth decided to adopt the Macintosh, the provost presented the plan to every single committee of which he was a member, but that does not mean that everybody welcomed the initiative. He and I had to endure a fairly rough session at a meeting of the university faculty and the president never really accepted that we had rejected his friends at IBM.

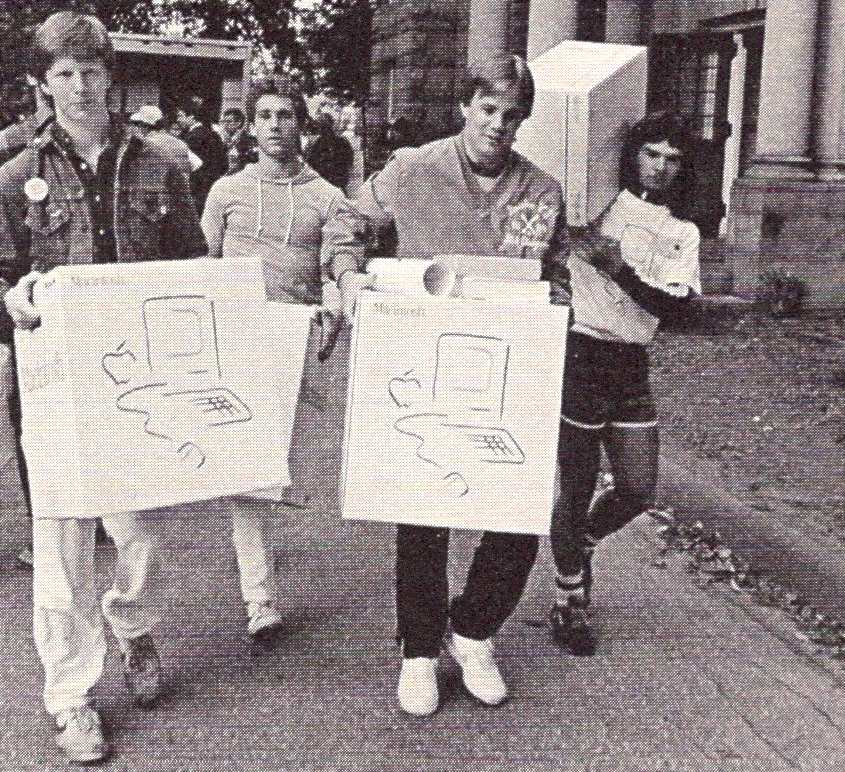

Dartmouth freshmen collect their Macintoshes

IN 1984, the standard package was a Macintosh with MacWrite, and MacPaint A communications package was delivered later. Many students also chose a carrying case and a printer. Students were urged to buy computers, and between 75 percent and 80 percent of the freshmen did so. Owning a computer was made a requirement in 1991, but it did not have to be a Macintosh.

© 1984 Stuart Bratesman - All rights reserved

The first year, 1984, was hectic. The resources of the computing center were focused on the arrival of the freshmen in September, but all the usual services had to be kept running. Converting the network to AppleTalk was a major engineering feat. At the same time, the telecommunications team had to wire the dormitories, install new nodes, and make the cables to connect Macintoshes to the wall outlets. The communications package of MacTerminal and the special cable was slightly late, but was delivered to the students a few weeks after the beginning of the term. Logistics were a challenge. The computing center had a small store selling manuals and supplies. This was transformed into a computer store supplying Macintoshes and IBM PCs, with their software and supplies. Technicians had to be trained in repair work. The handout of the computers to the freshmen was turned into an event, with a convoy of trucks delivering them from the warehouse.

For those of us who were advocates of the Macintosh, the challenge was to balance the long term potential against the deficiencies, which we hoped were short term. The enthusiasm of a few core faculty helped solve the shortage of good applications. Although the early Macintosh was an awkward machine to program, the quality of the QuickDraw tools enabled determined individuals to create good programs quite quickly. We were able to support them with the machines that we had received from Apple and grants from several private foundations.

Apple worked effectively to overcome many of the limitations without compromising the overall design. At the first meeting of the Apple University Consortium, Jobs spoke of the several developments, notably the plans for a small laser printer, which was the first for any personal computer. Extending the memory to four times its original size and adding a hard disk solved two crucial problems.

DarTerminal

This is a DarTerminal screen dump. It shows how Apple's Chooser could be used to connect to computers and services on the Kiewit Network.

Screen image by Rich Brown

Over the next few years Dartmouth used its technical resources to provide networked services that augmented those provided by Apple. The original MacTerminal was replaced by a more flexible program, DarTerminal, and the Avatar distributed editor was ported to the Macintosh. Dartmouth's Fetch program, an FTP client, is still going strong as a file transfer program for Macintoshes. A new mail system, BlitzMail, was so well received that there was dismay when it was withdrawn in 2011. A group of universities collaborated in providing AppleTalk service over dial-up telephone lines. Many of these developments took place after I moved to Carnegie Mellon in summer 1985.

The decision to select one type of computer and support it well proved a great success, but Dartmouth was never exclusively a Macintosh campus. IBM PCs were always preferred by the business school. Other individuals chose them or later the Windows clones. From the earliest days, the computer store sold IBM PCs and the computing center steadily extended the distributed environment to support them. Networked ports in the dormitories could be configured for asynchronous connections and later for Ethernet. BlitzMail and the Avatar were ported to the IBM PC. A report in 1991 estimated that there were about 10,000 computers on campus of which 90 percent were Macintoshes.